Did Methodological Individualism Get Lost in a Sea of Body Counts?

I. Austro-Libertarian Anti-War Analysis Feels Dangerously Keynesian: An Introduction

In the pantheon of libertarian principles, few shine as brightly as the commitment to peace. From the classical liberals who denounced imperial adventures to modern libertarians who marched against Vietnam and Iraq, the movement has consistently positioned itself as a voice against the machinery of war. This stance flows naturally from our core beliefs: if initiating force against peaceful individuals is wrong, then war, the ultimate expression of organized violence, must be among the gravest of evils.

Yet something curious has happened within certain corners of the libertarian anti-war movement. In their laudable zeal to oppose conflict, some have begun employing arguments that seem to contradict other fundamental libertarian principles. The same thinkers who would instantly reject collectivist reasoning in economics or social policy sometimes embrace surprisingly similar logic when discussing war. Those who normally insist on individual responsibility and careful analysis of who did what to whom can suddenly shift to speaking in aggregates: counting bodies, tallying destruction, and declaring moral equivalence between all parties to a conflict.

This essay offers an internal critique, a friendly intervention from within the libertarian tradition itself. The goal is not to weaken the anti-war cause but to strengthen it by ensuring our arguments remain consistent with our deepest principles. For if we abandon methodological rigor in our opposition to war, we risk undermining the very philosophical foundations that make the libertarian voice unique and valuable in debates about war and peace.

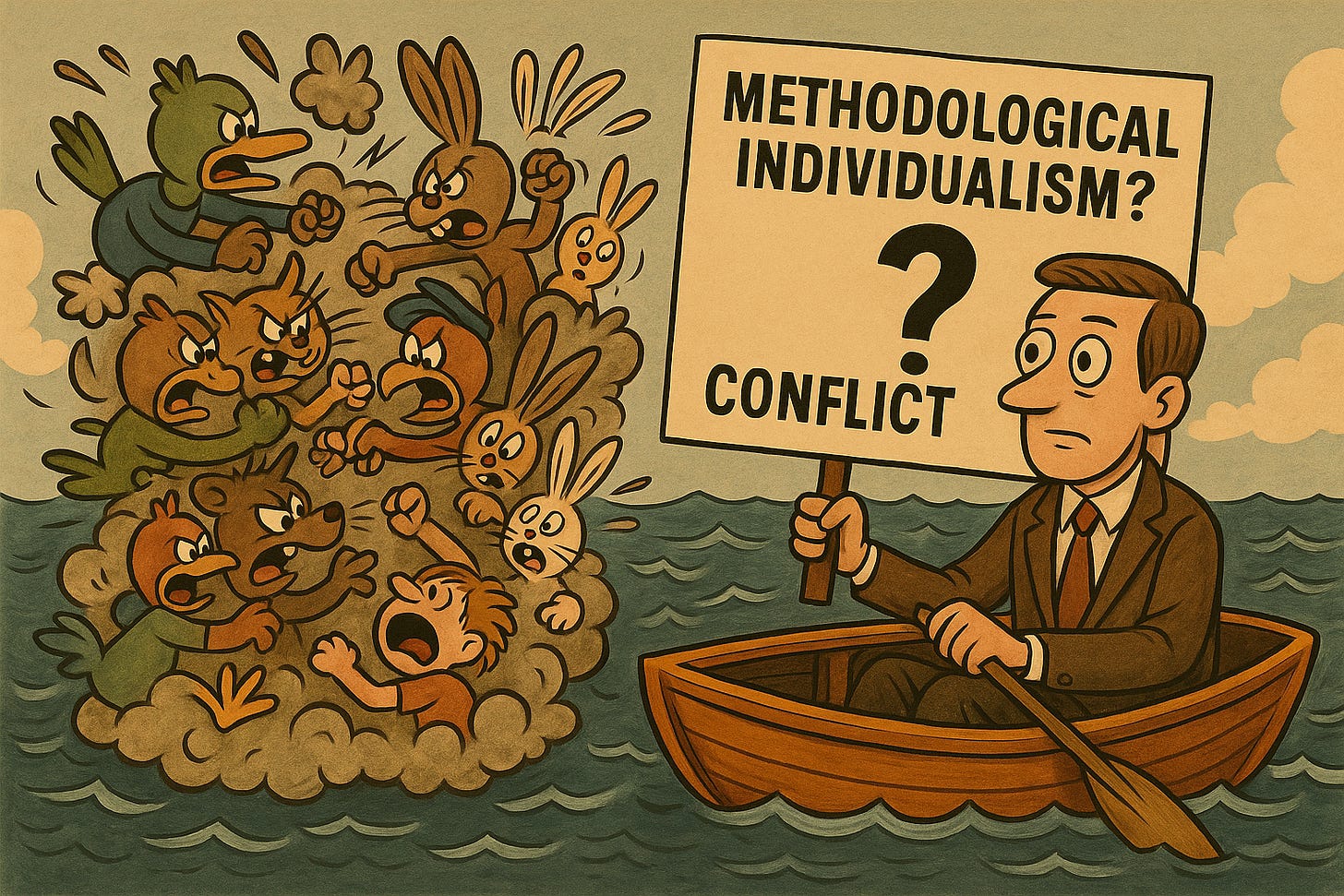

The specific concern is this: some contemporary Rothbardian anti-war rhetoric has drifted from methodological individualism (the idea that only individuals act and are morally accountable) into macro-aggregative, morally symmetrical language that treats all sides in a conflict as equivalent by focusing only on collective outcomes (body counts, destruction) instead of individual agency and actions.

This shift represents a curious parallel to the very Keynesian macro-logic that libertarians reject in economics. Just as Austrian economists criticize GDP and aggregate demand for obscuring individual choices and market processes,[1] I suggest we should be wary when anti-war arguments rely heavily on aggregate death tolls while ignoring the crucial distinction between who initiated force and who acted in defense. The central problem, therefore, is to assess whether this methodological error, so clearly identified in economic analysis, has crept into certain contemporary Rothbardian ethical analyses of war.

In the sections that follow, we will examine Murray Rothbard's foundational anti-war views and how the clarity of his principles can blur in practice, explore the shift from individualist analysis to aggregate moral symmetry, explain why flattening distinctions between aggression and defense is a mistake, highlight consistent approaches by thinkers like Walter Block, Ludwig von Mises, and F. A. Hayek, and apply these ideas to a modern conflict case study. The tone throughout is one of constructive criticism: a libertarian reclaiming of anti-war logic that stresses agency, context, and the initiators of force, without ceding an inch of the commitment to peace.

II. Rothbard's Anti-War Foundations

Any libertarian critique of war rightly begins with Murray N. Rothbard. Rothbard was one of the most vehement anti-war voices in modern libertarianism, viewing war as a brutal instrument of state power. He famously summed up the libertarian ethos with the stark dictum: "War is mass murder. Conscription is slavery. Taxation is robbery."[2] In Rothbard's view, war and the state are inextricably linked: "It is in war that the State really comes into its own: swelling in power, in number, in pride, in absolute dominion over the economy and the society."[3] War allows the state to expand its coercive dominion, crush civil liberties, and siphon resources under the guise of national crisis. Small wonder Rothbard concluded bluntly that "all government wars are unjust."[2]

For Rothbard, an unjust war was not simply one fought by the "bad guys"; rather, the very nature of interstate war, conducted by states through taxation, conscription, and mass bombardment, almost inevitably violates the nonaggression principle on a colossal scale. "The very nature of interstate war puts innocent civilians into great jeopardy, especially with modern technology," Rothbard observed.[2] Even a war fought for an ostensibly good cause can transgress libertarian ethics if it targets innocents or relies on coercive means.

Rothbard anchored his anti-war stance in methodological individualism and natural rights theory. Only individuals act; thus only individuals (be they soldiers or political leaders) are morally responsible for acts of aggression. The Non-Aggression Principle (NAP) forbids the initiation of force against persons or property; force is only justified as defensive or retaliatory against an aggressor.[4] Rothbard extended this principle to state warfare: a war can be just if and only if violence is strictly limited to aggressors. In theory, if State A's military attacks State B, B has the right to defend, but not by inflicting collateral damage on innocents or trampling the rights of its own citizens.

This is where Rothbard's purism led him to a very high standard for a "just war." In his essay "War, Peace, and the State," he argued that if a defending nation's government conscripts unwilling soldiers or bombs civilian areas in the process of fighting off an aggressor, it commits new crimes as grave as those of the original aggressor.[5] For example, Rothbard imagines an individual scenario: if Jones is being robbed by Smith, Jones may justly use force to stop Smith, but Jones may not bomb an entire apartment building to kill Smith, nor seize a neighbor's car at gunpoint to chase Smith down. Should Jones do so, "he is as much (or more of) a criminal aggressor as Smith is," Rothbard writes.[2]

By the same token, if Nation B in a "defensive" war resorts to conscripting its citizens (enslaving them) or carpet-bombing cities (murdering innocents) in order to stop Nation A's invasion, Rothbard would condemn those acts as criminal. B's cause may have been righteous, but it has forfeited moral purity by committing aggression of its own. As Rothbard tartly put it, "War, then, is only proper when the exercise of violence is rigorously limited to the individual criminals. We may judge for ourselves how many wars or conflicts in history have met this criterion."[2]

Rothbard's uncompromising logic ensures that even well-intentioned wartime leaders are held to the same moral law as anyone else: the ends (stopping an aggressor) do not justify means that violate rights. However, this absolutism can blur agency and context. In practice, nearly no modern war meets Rothbard's stringent criteria. Even World War II, often cited as a "just war," involved Allied transgressions (e.g. the firebombing of Dresden, the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) that Rothbard would label mass murder.

Rothbard did indeed criticize those Allied actions as deeply criminal, right alongside the crimes of the Axis powers. By focusing on the libertarian principle in isolation, he tended to treat any violation of rights as equally condemnable, regardless of who started the conflict. Thus, the moral agency of the initial aggressor (Nazi Germany or Imperial Japan) becomes somewhat blurred in Rothbard's analysis of WWII, because he emphasizes that the Allied governments also spilled innocent blood and "came into their own" as oppressive states during the war. The result is an optics of moral symmetry: both sides committed unforgivable acts against innocents, so both sides were criminal to some degree.

Rothbard's followers took this insight and, in some cases, ran further with it. Many "Rothbardian" libertarians after him have been stalwartly anti-war (often spearheading historical revisionism about U.S. wars, NATO interventions, etc.) and they sometimes echo Rothbard's tendency to condemn all belligerents in a conflict indiscriminately. What began as a rigorous application of the NAP (refusing to give a free pass to one side's collateral damage) can slide into a pacifist narrative that makes no moral distinction between, say, the Allies and the Axis, or between a terrorist group and the government it provokes. The agency of those who initiate force fades from view when every violation of rights is tallied on the same ledger. We can see this drift clearly in the rhetoric of some contemporary libertarian anti-war arguments, which we will examine next.

III. From Individuals to Aggregates

Libertarians pride themselves on methodological individualism in social analysis. As Ludwig von Mises articulated, "all actions are performed by individuals," and collective entities, such as "society" or "the state," do not act in themselves but operate only through the intermediary of individuals.[6] Friedrich A. Hayek similarly emphasized that social phenomena are constituted by the subjective beliefs, opinions, and knowledge of individuals.[6] Austrian-school economists reject macroeconomic aggregates as the primary datum; instead, they explain economic phenomena by the choices and actions of individuals.

The Austrian critique of macro-aggregates in economics provides a powerful analogy. Austrian economists argue that concepts like GDP, aggregate demand, and general price levels, while potentially useful as historical summaries, are misleading when used as the basis for economic theory and policy. These aggregates obscure individual plans and subjective valuations, ignore the heterogeneity of capital, conceal causal processes, and lead to flawed policy recommendations.[7] As Hayek's "fatal conceit" argument suggests, the belief that a central planner can possess and process the dispersed knowledge necessary to effectively manage an economy through aggregates is fundamentally flawed.[7]

Paradoxically, some libertarian anti-war arguments abandon that individualist lens and sound strikingly macro, focusing on aggregate outcomes like total casualties, much like the Keynesian statist logic libertarians otherwise reject. A hallmark of this rhetoric is a shift from discussing persons and their responsibilities to talking about war in terms of interchangeable victims and symmetrical suffering.

One often hears slogans such as "Don't trade one dead baby for another" in these circles. The intent is heartfelt (to oppose killing innocents anywhere) but notice the framing: it treats deaths as commensurate units ("one dead baby" on this side versus "another" on that side) to be weighed equally. The implicit message is that once bombs are falling and children are dying, it no longer matters who is doing what; all that matters is the body count. Such language reduces individual human lives to abstract counters in a macabre calculus. The cause of each death, the choices and agency behind each act of violence, drop out of the equation. All that remains is a tragic sum of innocents dead, with an insinuation that if one more child is killed on side X in retaliation for side Y, we have merely "traded" lives pointlessly.

This reasoning mirrors the very macro-aggregative approach libertarians criticize in other contexts. Consider how Keynesian economists speak of national income, employment levels, or "net gains," glossing over the heterogeneous individuals that make up those numbers. In Keynesian policy debates, one might hear: "It doesn't matter which businesses fail or which jobs are lost in restructuring; what matters is overall employment and GDP." Austrians rightly bristle at that, pointing out that aggregate outcomes cannot be divorced from the micro-level human actions and moral considerations (e.g. whose property is taken, who is forced to adjust) that produce them.[8] Yet, when some libertarians say "War killed 100 of their children and 100 of ours; we must stop the cycle of violence," they are, perhaps unwittingly, adopting a similar lens. They tally deaths like a grim GDP, focusing only on quantities of tragedy, rather than qualitatively distinguishing murder from self-defense.

Contemporary Rothbardian anti-war discourse often focuses on the perceived aggressions and imperialistic tendencies of the United States and its allies. For instance, Scott Horton has argued that the United States "provoked" Russia's invasion of Ukraine through NATO expansion and interference in Ukrainian politics.[9] Similarly, Ron Paul's "blowback" theory attributes events like 9/11 to prior U.S. government actions in the Middle East.[10] These arguments often emphasize the tragic human cost of war, frequently citing statistics of civilian casualties and widespread suffering.[11]

This use of aggregated data, such as death tolls and statistics on displacement or malnutrition, to underscore the horrors of war is very common. For example, Joshua Shoenfeld's article on LewRockwell.com concerning the Gaza conflict cites figures like "16,000 Palestinian children...killed" and projections of widespread malnutrition to paint a grim picture of the humanitarian crisis.[12] While such data are emotionally compelling and crucial for understanding the scale of human suffering, their use becomes problematic from a methodologically individualist standpoint if they are presented without sufficient disaggregation or context regarding individual circumstances, agency, or the critical distinction between combatants and non-combatants, and aggressors versus defenders.

To illustrate, consider a statement from a recent commentary defending "moral equivalence" between the deaths of children on opposing sides of a conflict. The author argues it's "misguided" to claim "a fundamental moral difference between how Hamas and the IDF kill children", positing that ultimately "the children die all the same."[13] In this view, what matters morally is the aggregate fact that children are being killed; any difference in intent or cause is deemed secondary. Whether innocents died because terrorists deliberately targeted them or because a defensive military action unintentionally caused collateral casualties is brushed aside as a mere "difference in institutional culture and public norms," a detail less important than the body count.

This aggregate-style moral accounting effectively treats war as a clash of collectives, not of individual actors making choices. It speaks of "children killed by the IDF" vs "children killed by Hamas," as if The IDF and Hamas were homogenous entities rather than organizations composed of distinct individuals with very different aims and methods. Gone is the libertarian's usual insistence on disaggregating the collective. (In any other policy area, libertarians remind us "society" doesn't act; only individuals do.) When it comes to war, however, some are quick to speak of what "Side A" and "Side B" as wholes have done, reducing myriad individual human actions into one lump sum of suffering.

Another subtle shift is from ethical language to accounting language. We hear talk of “trading lives” or “exchanging one atrocity for another,” as if morality were a zero-sum ledger based on interpersonal comparisons of pain and suffering. To the extent blame is assigned, it is generalized: "all parties are guilty of killing innocents, therefore all are equally condemnable."[14] The libertarian emphasis on pinpointing the aggressor (the one who broke the peace first) recedes. Instead of asking, "Which persons or units launched attacks and which responded? Did they target civilians or combatants? Under what constraints or warnings? What is their agenda? What is their ideology?", the macro approach just counts corpses.

In essence, what we see in this drift is methodological individualism being supplanted by methodological collectivism in some libertarian anti-war argumentation. The reasoning becomes outcome-centric: focusing on static states of the world (so many lives lost) rather than on human actions within that world (who did what to whom). It is eerily reminiscent of the consequentialist, aggregate thinking that libertarians usually reject, where only the final sum of utility or damage matters, and no agent in particular can be held accountable. The next section will argue that this approach is not only un-libertarian in method but also dangerous in its moral implications, because it collapses the vital distinction between aggression and defense.

IV. The Problem with Moral Equivalence

Libertarian ethics, rooted in the Non-Aggression Principle, holds a clear distinction: the initiator of force (aggressor) versus the responder to force (defender). Aggression (the unjust initiation of violence) is categorically illegitimate, while defensive force (violence used to repel or punish an aggressor) is legitimate, even though regrettable.[4] This distinction lies at the core of libertarian justice, not just in language but in principle. As Stephan Kinsella's estoppel theory elucidates, an aggressor, through their act of aggression, is "estopped" or prevented from consistently objecting to defensive force being used against them, as their actions have implicitly affirmed the legitimacy of using force.[15] However, the pacifist or morally symmetrical rhetoric creeping into some libertarian circles blurs this line. By treating all uses of violence as equal, it commits a grave moral error: it equates murder with self-defense, and thereby, perhaps unintentionally, gives the aggressor a free pass.

Why is defense ≠ aggression such an important distinction? Because without it, the entire libertarian theory of rights crumbles. A crime victim who fights off his attacker is using force, yes, but to call him equally guilty of "violence" as the attacker is a profound injustice. Libertarians intuitively understand this in domestic contexts. Yet, when it comes to war, some hesitate to apply the same logic. The result is a language of "moral equivalence" or "both-sides-ism" that essentially says: "Violence was used by all sides, therefore no side is morally superior."

This is wrong. Defense is not aggression, even though both involve force. As Alan Futerman (a libertarian scholar) aptly put it in a recent discussion: "Many libertarians are unfortunately conflating two concepts. One is aggression and the other is the use of force. Defense involves the use of force, but it does not entail aggression... self-defense involves the use of force but is the opposite of aggression."[16] In other words, not all violence is created equal. The difference lies in who initiated the conflict and who is reacting to that initiation.

When pacifist discourse focuses only on outcomes ("people are dying") and ignores who made that outcome necessary, it effectively flattens moral reality. It's akin to observing a police officer and a mugger exchange gunfire and tut-tutting that "both are engaged in violence," technically true, but deeply misleading when assigning responsibility. As Sam Harris (critiquing the "moral equivalence" view) noted, "Counting dead bodies isn't sufficient... you must count intentions to judge the morality of the 2. We [must consider] who rejoices in massacres vs. who seeks to avoid killing innocents."[31]

The intentions and actions leading to those bodies matter immensely. Did one side deliberately target civilians, or did they try to minimize harm? Did one side start a war of conquest, while the other mobilized to resist? These questions are central to any moral assessment, and libertarianism, with its focus on individual intent and consent, is uniquely positioned to ask them. Ignoring these factors means abandoning our principles of justice.

Moreover, pacifist moral symmetry has a perverse practical effect: it incentivizes aggression. If an aggressor knows that any retaliation will earn equal moral condemnation for the defender, the aggressor gains a one-sided advantage. Imagine a norm where if Country X attacks Country Y, but Y fights back and damage occurs on both sides, the world will scold both equally for "perpetuating violence." That norm effectively encourages Country X to strike, secure in the knowledge that its opponent cannot hit back without being branded just as bad. As economist Bryan Caplan has pointed out, a blanket pacifist stance "actually increases the quantity of war by reducing the cost of aggression." The cost is reduced because the aggressor can rely on the victim's restraint or on external pressure for "ceasefires" that freeze gains in place. A historical example might be how Nazi Germany would have loved a situation where the Allies, after being attacked, refused to fight because war is evil; Hitler's invasions would have met little resistance.

F. A. Hayek and other classical liberals understood that absolute pacifism (refusing to ever take up arms) can enable tyranny. In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek warned about the dangers of failing to resist threats to liberty. He famously stated, "As is true with respect to other great evils, the measures by which war might be made altogether impossible for the future may well be worse than even war itself."[17] This suggests that an absolute pacifism that allows tyranny to flourish could lead to a greater evil than a defensive war undertaken to preserve liberty. In the 1930s, the Allied policy of appeasement, driven in part by pacifist public sentiment after World War I, emboldened Hitler's expansion. As Winston Churchill bitterly quipped, "An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last."

Libertarian thought is not contrary to that insight; indeed, Ludwig von Mises observed that democracies which love peace can ill afford to simply disarm unilaterally in the face of militaristic regimes. Mises noted that "nations are fundamentally peaceful... They accept war only in self-defence; wars of aggression they do not desire. It is the princes [i.e. governments] who want war".[18] But because aggressor governments exist, defenders must sometimes fight. It is crucial, however, to place moral blame where it belongs: on those who made war inevitable.

When defensive forces inadvertently harm innocents, a humane person rightly mourns those deaths, but the moral onus for such tragedy still lies with the side that initiated the aggression and created the deadly situation. Golda Meir, Israel's former Prime Minister, captured this sentiment poignantly (though not a libertarian, her logic fits libertarian ethics): "We can forgive the Arabs for killing our children, but we can never forgive them for forcing us to kill their children." The horror of being forced into a position where defensive killing occurs is itself an aggression committed by the initiator.

Libertarians must be careful here. None of this is to glorify war or excuse truly unjust acts committed in war by the "good guys." It is only to maintain moral clarity. A defensive war can still be prosecuted unjustly in its tactics, and those specific injustices should be condemned, but that does not erase the fact that one side's cause (repelling invasion or genocide) is just, while the other's cause (conquest or aggression) is unjust. Collapsing those categories undermines the libertarian principle of justice because it treats deliberate aggressors and reluctant defenders as morally interchangeable.

Pacifist moral equivalence ignores agency, context, and initiation of force, three things libertarians usually emphasize. It amounts to saying, "It doesn't matter who dropped the first bomb or why; violence is violence." But to a libertarian, it matters immensely who violated rights first. Yes, we want to minimize total violence, but the surest way to do that is to deter and defeat aggressors, not to handcuff defenders and let aggressors carry on unopposed. As we will see next, many prominent libertarians have in fact upheld this nuanced, principled view, resisting the drift into symmetrical rhetoric. They demonstrate that one can be firmly anti-war and still maintain that justice is asymmetrical in any conflict: it sides with those acting in rightful self-defense over those committing aggression.

V. Clarifying the Positive Model: Block, Mises, Hayek, and Others Who Stay Consistent

Not all libertarians have succumbed to the lure of moral symmetry. This section focuses on the few who reject moral flattening and keep their anti-war arguments consistent with individualist principles. These thinkers show that it's possible to abhor war's carnage while still saying: this side in this conflict is in the right (defensively), and that side is in the wrong (aggressively). They offer a template for, what I believe to be, an internally consistent libertarian peace advocacy.

Walter Block: Defense of Defensive Force

Walter Block, a noted Rothbardian economist and ethicist, has been outspoken in distinguishing legitimate defensive violence from illegitimate aggression. Block emphatically rejects the notion that libertarianism entails pacifism. "Libertarianism doesn't require pacifism. It's compatible with it, but it doesn't require it," he explains.[19] In the context of war, Block argues that one must scrutinize the conduct and aims of each side.

For example, in the Israel-Hamas conflict of 2023, Block points out that Hamas explicitly aimed to massacre civilians, an aggressive war crime, whereas the Israeli Defense Force, while using force, sought to avoid killing innocents and expressed regret when civilians were unintentionally harmed.[16] Yes, civilians died in Gaza due to Israeli strikes, a tragedy. But Block contends it is a crucial moral difference that Israel's military "drops leaflets warning civilians to evacuate" and tries to target combatants, whereas "Hamas purposefully aims at civilians".[16] He famously stated: "Whenever there's a war, there's got to be collateral damage. And if you say collateral damage means genocide, well, then you're a pacifist."[20]

In other words, equating unintended collateral damage with the purposeful genocide of civilians is a category mistake, one that only a strict pacifist (who rejects all use of force categorically) would make. Block's view reflects classic libertarian thinking: that context and intent matter. Using force to stop a would-be genocider is not only permissible, it can be morally obligatory, even if sadly some innocents get caught in the crossfire. The blame for those innocents' deaths, Block would stress, lies primarily on those who initiated the aggression and created a battlefield among civilians (in this case, on Hamas for launching war and also using civilians as shields).[21]

Block's clarity on this has led him, controversially, to support the idea that complete victory over aggressors can be the most humane outcome in the long run. Paraphrasing a point from Block and Alan Futerman's recent work: a classical liberal, even an anarchist, can recognize that a state under attack "has a moral right and a moral duty to protect its citizens and end [the] threat once and for all", rather than perpetually "trading casualties" under a misguided notion of restraint.[16] This is said not to endorse state power per se, but to apply the principle of defensive force to real-world conditions. Block stands as a modern exemplar of how to be anti-war (he wants Hamas and any hostile forces to cease to exist, not for war to continue) without being indifferent to agency. He focuses on rights violations (who is violating whose rights) rather than just on the body count.

However, Block's application of these principles has not gone unchallenged. Hans-Hermann Hoppe, in an open letter, accused Block of abandoning methodological individualism and libertarian principles in his defense of Israel.[22] Hoppe argued that Block's justification for Israeli land claims relied on collectivist notions (e.g., group property rights based on ancient lineage or genetic similarity) and that his call for Israel to do "whatever it takes" to destroy Hamas amounted to an endorsement of the "indiscriminate slaughter" of innocents, violating the NAP. Hoppe, applying his own MI-consistent analysis, condemned both Hamas and the State of Israel as "gangs" financed by extortion and called for peace and diplomacy, with individual perpetrators of violence to be dealt with through "regular police-work" rather than indiscriminate military action.[22]

For the reasons outlined earlier, including moral asymmetry and true methodological individualism, I believe libertarians should reject Hoppe’s stance as well.

Ludwig von Mises: Individualist Analysis in International Affairs

Mises, as an older contemporary of Rothbard, was in many ways an intellectual forefather of libertarian anti-war sentiment. Having lived through the World Wars, Mises saw first-hand the devastation statism unleashed. He strongly championed liberal internationalism: the idea that free trade and respect for national self-determination would eliminate most motives for war. Mises condemned aggressive war in no uncertain terms: "War...is harmful, not only to the conquered but to the conqueror... Peace and not war is the father of all things."[23]

Yet, Mises was not a naive pacifist. He understood that peace sometimes must be defended by force against would-be conquerors. One of Mises's most powerful statements comes from his book Socialism, where he differentiates the people's desires from their rulers' ambitions: "Nations are fundamentally peaceful... They accept war only in self-defence; wars of aggression they do not desire. It is the princes who want war... It is the business of the nations to prevent [the princes] from achieving their desire."[18] Here, Mises asserts that when wars happen, we should ask: did the people accept this war out of true self-defense, or was it foisted on them by a ruling clique pursuing power? This aligns perfectly with methodological individualism: identify the actual actors (the aggressors in government) and the motives.

Mises also explicitly rejected the idea of equal blame in cases of clear aggression. During World War II, Mises, who had to flee the Nazis, supported the Allied war effort as a necessary fight to destroy totalitarianism. In Omnipotent Government (1944), written as the war raged, he praised the Allied cause as morally noble. "This aim alone can elevate the present war to the dignity of mankind's most noble undertaking. The pitiless annihilation of Nazism is the first step toward freedom and peace," Mises wrote.[24] Consider his profound statement: Mises viewed the war to defeat Hitler not a regrettable gray zone, but "mankind's most noble undertaking" given the circumstances, because it was a war to end a monstrous aggression and restore liberty. He did not say this lightly; he was keenly aware of war's costs, but he placed responsibility squarely on the Nazi regime's aggression.

Notably, in the same passage, Mises addresses concerns about atrocities on both sides by essentially saying: do not lose sight of why this war is being fought. Dwelling on whether Allied bombing in World War I was worse than Nazi bombing now, or tallying mutual sins through history, is, Mises argued, "without any relevance to the problems of our time".[24] The urgent task is to stop the current aggressors and prevent such outrages from ever occurring again. Mises therefore maintained both an anti-war ideal (he wanted a world of peace and free cooperation) and a recognition that when war is forced upon you by aggressors, you must fight decisively and end the threat. He never succumbed to the lazy equivalence of blaming France and Britain for "also engaging in war" against Germany; he knew Hitler's regime was uniquely culpable for unleashing the orgy of violence, and that ending that aggression was a prerequisite for a just peace.

Friedrich A. Hayek: The Dangers of Pacifism Enabling Tyranny

Hayek, another Austrian economist and classical liberal, is known for his writings on knowledge and tyranny, but he also lived through WWII and reflected on the follies that led to it. Hayek recognized that well-intentioned "peace at any price" attitudes in Britain had ironically made war more likely. Though not as outspoken on war ethics as Mises or Rothbard, Hayek implicitly endorsed the idea that failing to resist evil leads to worse outcomes. In The Road to Serfdom, he notes how the desire to avoid conflict and the intellectuals' infatuation with planning opened the door to totalitarianism, a different angle, but one that resonates with our theme.[25]

Other classical liberals of Hayek's time, like the French philosopher Étienne Gilson, famously warned that "to desire peace at any price is a great danger" because it tells aggressors that their price will be paid. Hayek shared the view that liberty sometimes must be defended by force. He certainly did not believe, for instance, that it would have been better for Europe to surrender to Nazi Germany in order to avoid the Blitz and the Battle of Britain. Indeed, Hayek admired the British resolve once the war began. In 1940, as an emigrant in London, Hayek witnessed a society choosing to fight rather than capitulate. While he critiqued certain war socialism policies, he supported the overall war effort against Hitler.

In short, Hayek's consistent liberalism held that peace is the highest ideal, but not an unconditional one. A "peace" that is merely the absence of resistance to tyranny is no peace at all; it is slavery. Libertarians in Hayek's vein emphasize that one must distinguish a just peace from a false peace. A just peace is one where rights are respected and aggression is absent; a false peace is "no one shooting because the conqueror has already won." Thus, Hayek would caution libertarians today not to let pacifist rhetoric cloud the reality that sometimes force must meet force to safeguard a free society.[26]

Others (Clarence Carson, Leonard Read, Walter Block's contemporaries)

Many other libertarian or Old Right thinkers have maintained this balance. Leonard E. Read (founder of FEE) was staunchly anti-war but also penned essays during the Cold War noting that a free society has a right to defend itself against communist aggression. The late Justin Raimondo (of Antiwar.com, a Rothbardian) often excoriated U.S. imperialism, but even he did not claim no difference between, say, Al Qaeda and the victims of 9/11's response. He simply urged the U.S. to stop intervening where it was itself the aggressor. Ron Paul, another prominent libertarian, has opposed nearly all U.S. foreign wars as unjust, but if pressed, he acknowledges the moral difference between an invader and one who fights back on home soil.

The common thread among these consistent voices is clarity: they identify who the aggressor is in any given situation and do not shy from saying that aggression is the root of the evil. They focus on individual actions: e.g., which leader or faction made the decision to break the peace. They also stress proportionality and the importance of not harming innocents, but crucially, they understand that when innocents do tragically die in a defensive effort, the ethical analysis must still track back to who lit the fuse.

As Walter Block and Alan Futerman wrote recently, reflecting on World War II, it's misguided to speak as if German cities suffering defeat was some arbitrary tragedy -- "those who were part of the Nazi war machine did not experience 'some horrific military defeat' but got what they deserved as a consequence of what they initiated".[16] It is a reminder that context matters: Nazi aggression brought about Germany's ruin. Likewise, Block and Futerman apply the same logic to present conflicts: "The Nazis then, as Hamas and its supporters now, had agency. And they brought their own destruction on themselves."[16] This is a powerful reassertion of the libertarian view that individuals and groups choose aggression and thereby invite forceful backlash, which cannot be morally equated to the initial aggression.

In highlighting these consistent approaches, we see a path forward for libertarian anti-war advocacy. One that upholds peace as a goal without sacrificing the principle of justice. These thinkers demonstrate that one can support peace through strength (or through non-intervention, as context dictates) while always keeping moral score: who is defending, who is aggressing. They offer plenty of quotes and examples to fortify the case that we must not let a laudable desire to end war morph into a blanket refusal to assign any blame in war. Instead, libertarians should do what we do best: analyze the cause and effect at the human-action level. Who fired the first shot? Who is targeting innocents? Who would stop if the other side stopped, and who would continue to aggress? These are the questions that separate a rigorous, libertarian anti-war position from a feel-good, pseudo-"even-handed" pacifism that ultimately betrays the innocent.

VI. Anticipating and Rebutting Objections

A thoughtful libertarian (or pacifist critic) might raise several objections to the position I’m taking. It's important to address these head-on:

Objection 1: "All state warfare is immoral and illegitimate, full stop. States themselves are aggressors against their own people (through taxation, etc.), so how can we side with any state in war? It's just gang vs gang, with civilians caught in the middle. Therefore, it's best to oppose all sides in any war and demand an immediate end to violence."

Rebuttal: It's true that libertarians view states as institutionalized aggressors in many ways (taxation being theft, conscription being slavery, etc.).[28] And indeed, if two states are fighting a purely expansionist war over turf, a pox on both their houses. But not all wars are morally equal. Even accepting that states are not ideal proxies for justice, in a given war one state may be clearly in the role of aggressor against another society, while the other state's forces, however flawed, are performing a defensive function that someone has to perform. As Walter Block has argued, we must not let "sectarian anarchist" purity blind us to real-world distinctions.[19]

If we reflexively declare "all government wars unjust" without looking at context, we arrive at absurd implications -- for example, that it was unjust for the U.K. and U.S. to fight Hitler's Germany, or for South Korea to resist North Korea's invasion in 1950, or for a hypothetical libertarian micro-nation to use force repelling a totalitarian invader because, after all, they'd have to form some defense force (which might look 'statist'). Rothbard himself, despite his blanket statements, did at times acknowledge the aggressor/defender difference. The proper libertarian stance is: yes, war is hell and the state makes it worse, but if war has been thrust upon a people, it is not immoral for them to defend themselves -- even if they must do so via a state apparatus (since that's sadly what exists).

One can consistently hold that the state is an aggressor in general and that in a particular war, that state's military might be repelling a greater aggressor. To use an analogy: I disapprove of police departments enforcing victimless crime laws, but if a policeman stops a murder in progress, I won't say he acted illegitimately because he's part of the state. In war, context is everything. Labeling all state warfare "immoral" without nuance leads to moral paralysis where libertarians could not even morally endorse an action to stop genocide unless done by private militias. That's an untenable purity that effectively means surrendering the world to the worst actors. We can oppose war in general as a barbaric institution and still say, in specific cases, one side's violence is a just response to the other's evil.

Objection 2: "Even if one side started it, both sides are killing innocents now. Isn't a life an absolute value? How can you justify any further killing once innocents are at risk? Doesn't the fact that innocents will die mean we must call for an immediate ceasefire, no matter what, because nothing is worth the death of a child?"

Rebuttal: This objection tugs at the heartstrings and indeed reflects a noble sentiment: the pricelessness of each human life. Libertarians certainly agree that one should do everything possible to avoid harming innocents. The use of force must be highly discriminating. But consider the logical consequence of saying "nothing is worth the death of a child, therefore stop fighting immediately." If an aggressor is still in the field committing atrocities, halting all defensive operations will not save lives in the long run; it will cost many more lives. A ceasefire is not magic; it's just a pause or end to formal hostilities. If the aggressor retains capability and intent, they may use a ceasefire to regroup and strike again (or continue oppression).

Sometimes, tragically, the only way to ensure more children (and adults) don't die in the future is to take decisive action now -- even knowing some innocents could die despite our best efforts. It's the awful reality of situations like World War II, where failing to stop Nazi Germany early (in the name of peace) led to a conflagration that killed millions of children. Libertarians are not utilitarians who blithely trade lives on a ledger; we hold that no innocent should ever be intentionally killed. But we also recognize the concept of culpability. If one side is using civilians as shields or has woven itself into an urban population, and continues to aggress, the responsibility for the inevitable innocent deaths lies with those who made that situation.[21]

It is harsh but true: sometimes inaction in the face of aggression results in far greater slaughter of the innocent. Mises wrote about "the pitiless annihilation of Nazism" as a terrible but necessary step to secure a future peace.[24] He didn't say that lightly; he meant that if you let such an evil survive out of reluctance to cause collateral damage, you would eventually get a world with much more death and no freedom. Libertarians are realists about human action: we know trade-offs exist. The key is that any defensive violence must be restrained by strict norms: use minimal force necessary, avoid non-combatants as much as possible, and so on. If those norms are followed, then the unfortunate deaths that occur are on the aggressor's head. Saying "one dead child is too many, so stop now" may seem humane, but what if stopping now sets the stage for ten more dead children next month? These are brutal calculus forced on us by aggressors, not chosen by defenders. The most humane course can sometimes be to finish the fight quickly and remove the threat.

Objection 3: "By picking a side or saying one side is 'just,' aren't we sliding into nationalism or statism? Libertarians should be above these worldly squabbles and stick to principle -- war is the health of the state, violence is tragic, end of story. Otherwise we risk becoming court philosophers for governments ('our military good, their military bad')."

Rebuttal: There is a difference between sober moral analysis and jingoistic cheerleading. Saying "in this conflict, side X is in the right because it is acting in self-defense" is not nationalism; it's principle. Nationalism would be saying "side X is inherently right because it's our country (or our favorite nation)." We are not advocating blind support for any government's war. We are advocating conditional support for the individual rights being defended by some people (who may happen to wear a government uniform) against aggression by others.

Libertarian British citizens in 1940, for instance, could support Britain's defense against Nazi Germany not because they love the State or Churchill, but because the alternative was conquest by a genocidal totalitarian regime -- clearly a worse outcome for liberty. As long as we keep our reasoning grounded in who is violating rights, we won't fall into blind nationalism. In fact, libertarians should feel equally comfortable condemning their own government's military if it is used for aggression. Many of us did exactly that with the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 -- a war where the U.S. was the clear aggressor on a false pretext. In that case, being anti-war and refusing moral equivalence meant pointing out that Iraqi fighters resisting U.S. invasion were more justified than the invading forces (though we may loathe the Saddam regime, the invasion violated Iraqi sovereignty and killed countless innocents). There, the libertarian position was "this war is unjust and one-sidedly caused by the U.S. government." Far from being unprincipled, this is applying the same standard across the board.[29]

So, when a different conflict arises where, say, Russia invades Ukraine (to take another example), we logically apply the standard: Russia is the aggressor, Ukraine's defense is justified. That doesn't make us flag-wavers; it only makes us consistent defenders of the non-aggression principle. True, war is the health of the state -- it enlarges state power -- and we should always be wary of propaganda.[3] But sometimes one must choose the lesser evil: a temporary increase in state activity to defeat an aggressor may be a price worth paying to avoid permanent subjugation. The key is to watch like a hawk that our own state relinquishes emergency powers after, etc. History shows that doesn't always happen, and libertarians should indeed criticize war-induced power grabs (censorship, surveillance, etc.). But that is a separate issue from the justice of repelling aggression. We can multitask: oppose the enemy's aggression, and oppose our state's opportunistic overreach, both at once.

Objection 4: "Libertarians should be pacifists. The NAP implies a kind of pacifism. If we truly value consent and peace, how can we condone killing at all? Doesn't violence always beget more violence? What about the example of successful nonviolent resistance (Gandhi, MLK)? Shouldn't we hold ourselves to a higher standard and find nonviolent solutions even to violent problems?"

Rebuttal: Libertarianism is a philosophy of non-aggression, not non-violence per se. This is a crucial distinction. We abhor the initiation of violence, but we uphold the right of self-defense.[4] A pacifist might say: "Better to suffer harm than to do harm." A libertarian says: "It is better if no one does harm, but if someone attacks, the victim has the right to stop them, even if it requires defensive harm." There is no contradiction in valuing peace yet defending defense. Think of it this way: if you truly value innocent life and liberty, you cannot allow an aggressor to walk over others. Sometimes forceful resistance is what protects the values of peace and freedom in the long run.

Nonviolent resistance works under certain conditions -- mainly when the aggressor has some moral scruples or public relations vulnerability. Against a totally ruthless opponent (say, an ISIS or a Nazi), unarmed protest will simply be massacred and forgotten. Libertarianism doesn't require martyrdom to evil. It certainly respects those who choose personal pacifism (you are free to let someone harm you without fighting back, that's your choice), but it doesn't impose that as a moral duty on everyone, especially not in protection of others. As Walter Block noted, pacifism is compatible with libertarianism (you can be a libertarian and personally vow nonviolence), but it's not required.[19]

In fact, Murray Rothbard wrote a critique of pure pacifism, pointing out that a pacifist who would not even call the police or lift a finger to stop a murder in progress is effectively abetting aggression.[2] The proper ethical stance is that initiating force is wrong, but using force to thwart a wrongdoer is a virtue (or at least a right). History's examples of nonviolent movements are often cherry-picked; for each Gandhi there are cases where unarmed people were just crushed (Tiananmen Square protests, for example). Gandhian resistance worked partly because the British, for all their faults, had some accountability and eventually weariness; try that under Stalin and the outcome would be different.

Libertarians are not interested in moral exhibitionism ("look, I'd rather die than harm anyone, aren't I pure"). We are interested in justice and liberty prevailing. If that means some violent men must be met with violence, so be it. We impose limits -- e.g., we reject total war that targets civilians -- but we do not tie the hands of the innocent out of a misplaced idealism. Ultimately, the motto is "Peace, when possible -- but liberty and justice at all costs."[30]

By addressing these objections, we reaffirm that the stance advocated here is neither pro-war nor hypocritical. It is an internal critique aimed at rescuing libertarian anti-war thought from sliding into reflexive pacifism or sloppy equivalence. The goal is to keep our analysis rooted in cause and effect, aggression and defense, individual rights and responsibilities. Only by doing so can libertarians credibly advocate for peace and for justice -- since a lasting peace is born from the triumph of justice, not from the mere silencing of guns while injustice prevails.

Objection 5: "Austrians cite aggregates all the time. Rothbard used stagflation statistics to critique Keynesianism, Mises regularly employed empirical data. The key is that theory comes first, with data serving to check and revise. Similarly, citing war casualties doesn't constitute methodological collectivism. The practical reality is that modern terrorist organizations don't line up on battlefields; they embed among civilians. When theory demands avoiding civilian casualties through targeted operations (like Richard Ebeling's bounty proposal for Bin Laden), empirical reality shows this is often impossible. Winning against embedded terrorists is primary; avoiding casualties is preferable but not always feasible. Demanding pure methodological individualism in war analysis seems impractical given these constraints."

Rebuttal: This objection illuminates important distinctions about theory, empirics, and practical constraints that merit careful consideration, yet it misses how citing aggregates without examining underlying individual actions constitutes the very methodological error it seeks to defend.

First, regarding Austrian use of aggregates: Austrians indeed cite GDP, employment figures, and other macroeconomic data regularly. The crucial distinction lies in how these figures function analytically. When Rothbard wielded stagflation statistics against Keynesianism, he wasn't treating aggregates as primary theoretical constructs but as symptoms of underlying individual actions and government interventions. The data falsified Keynesian predictions, but the Austrian theoretical critique (that aggregates obscure individual choice and calculation) remained primary. Even Keynes himself, as Hayek noted, understood his theory as addressing specific post-WWI British conditions rather than providing a universal framework.[32]

The parallel to war analysis is precise: citing casualty figures isn't inherently collectivist. The methodological error occurs when these figures become the primary basis for moral judgment, divorced from individual agency and intent. When analysis reduces to "both sides have killed 100 children, therefore both are equally culpable," it commits the same error as Keynesian reasoning that treats GDP movements as causally decisive while ignoring underlying individual actions.

Second, concerning practical constraints of asymmetric warfare: Modern terrorist groups indeed deliberately embed themselves among civilians, making "clean" targeting nearly impossible. This reality demands more methodological individualism, not less. The individual agents who choose this strategy, knowing it will result in civilian casualties, bear primary moral responsibility for creating conditions where defensive forces face impossible choices.

The bounty proposal for Bin Laden illustrates the complexity. The relevant question isn't merely eliminating one individual, but dismantling terrorist capacity. When Bin Laden died, Al Qaeda simply appointed new leadership. Methodologically individualist analysis examines: Which individuals made which strategic decisions? Who chose to use human shields? Who attempted to minimize civilian casualties within operational constraints? Who celebrated versus mourned civilian deaths?

Third, on balancing principles with necessities: Accepting that defeating embedded terrorists takes priority doesn't require abandoning individualist analysis; it demands its rigorous application. As explored in recent voluntaryist scholarship, legitimate defense requires examining both mens rea (intent) and actus reus (act).[33] When defensive forces accidentally kill civilians while targeting combatants who deliberately hide among them, the intent differs fundamentally from forces that intentionally target civilians. This isn't mere "institutional culture" but the core distinction between legitimate defense and murder.

Body counts alone cannot determine moral action without examining intent and agency. A police officer who kills an armed robber and the robber who initiated violence may both have "body counts," but this doesn't make them morally equivalent. The homicide in self-defense isn't murder precisely because of the difference in agency and intent.

Without an objective metric or reasonable heuristic to delineate when someone's actions move beyond justified defense, there is no "compared to what?" for philosophical analysis. A methodologically consistent framework for evaluating defensive action would examine:

Initiatory agency: Who chose to break the peace first?

Intentionality: Are civilian casualties the goal or an unintended consequence?

‘Proportional’ necessity: Is the defensive response calibrated to stop the threat with minimal harm?

Discriminatory effort: Does the defender attempt to distinguish combatants from non-combatants within constraints?

Strategic embedding: Has either side deliberately placed civilians in harm's way?

This framework requires examining individual decisions and actions, not merely counting bodies. When defensive forces warn civilians, attempt targeted strikes, and express regret for unintended casualties, while aggressors celebrate civilian deaths and use human shields, these represent qualitatively different moral phenomena regardless of similar casualty figures.

The crucial "compared to what?" question must be answered: If the alternative to imperfect defensive operations is allowing continued aggression, then some level of unintended harm may be the lesser evil. But this judgment requires analyzing specific actions by specific agents, not treating "collateral damage" as an undifferentiated aggregate.

Acknowledging practical constraints doesn't require abandoning methodological individualism; it requires applying it more rigorously. Just as Austrian economists use empirical data without becoming Keynesians, war analysis can discuss casualty figures without becoming collectivist. The key is maintaining focus on individual agency, choice, and moral responsibility even when analyzing complex aggregate phenomena. Only through such analysis can we move beyond simplistic body counts to examine the human actions that create them.

VIII. Final Thoughts

I will say it again: libertarianism is, at its heart, a philosophy of peace. We seek a world where individuals interact through voluntary exchange and cooperation, not through force and coercion. In that sense, authentic libertarianism is deeply anti-war. It was Rothbard who taught us that of all state activities; war is the worst. It’s a mass murderous assault on life, liberty, and property on a scale nothing else can match.[2] Nothing in this essay should be construed as diminishing the libertarian commitment to ending wars. However, as we have argued, being anti-war must not mean abandoning logic, context, and principle. Paradoxically, a libertarian who opposes war effectively must be willing to analyze wars dispassionately to identify their causes and would-be solutions.

What I set out to critique was the internal contradiction that arises when some libertarians drift from methodological individualism to a kind of macro-collectivist pacifism. That contradiction manifests as rhetoric that sounds more like a utilitarian humanitarian NGO than a libertarian scholar; talking about aggregate death tolls and mutual destruction without reference to who is doing what to whom. It's the equivalent of a libertarian economist suddenly embracing GDP planning: it just doesn't fit our framework. We have seen how Rothbard's own rigorous principles, if applied without nuance, can lead to a flattening of moral agency -- but also how Rothbard's successors like Walter Block have shown a way to retain nuance and moral differentiation even while opposing war categorically in general.

Restoring libertarian rigor to anti-war arguments means re-emphasizing the primacy of the individual, both as the moral unit and as the unit of analysis. We judge actions, not collectives. We care who started an altercation and who retaliated. We value intentions and qualitative choices, not just quantitative outcomes. And we always ask, "Compared to what?" When someone demands an end to violence, we ask: what will happen if the other side's violence goes unanswered? When someone bemoans the death of innocents, we ask: who set in motion the events causing those deaths and how do we prevent far more innocents from dying in the future?

By injecting this clarity, libertarians can avoid the moral faux pas of false equivalence. We can stand firmly against interventions, empires, and aggressive wars (like Rothbard did opposing the Vietnam War and others), while still affirming that not all violence is morally equal. A libertarian Europe under attack by a fascist power should defend itself; a libertarian community confronted by a criminal gang should too. These are not betrayals of peace, but defenses of it. Friedrich Hayek warned that civilizations that lose the will to fight for their values may fall to those who haven't.[17] Libertarians want a world where that fighting isn't necessary -- but to get there, we sometimes have to countenance force to stop aggressors. This is the difference between pacifism and peace through strength.

Libertarians must remember that the individual, and not the death toll, is the truest moral unit. Every war is, tragically, made up of individual crimes (by aggressors) and individual acts of courage (by defenders). Our job is to never lose sight of that, and maintain methodological individualism across all domains. Just as Austrian economists understand the limitations of aggregate statistics while still using them carefully in Economics, libertarians can oppose war while maintaining moral clarity about who bears responsibility for violence.

We should neither collectivize guilt ("all soldiers on all sides are equally murderers") nor collectivize victimhood ("war just victimizes everyone involved equally"). Instead, we assign guilt and victimhood as the facts warrant, and usually, those facts show that some individuals (leaders, aggressors) victimized others (civilians, defenders). By keeping our focus on individual agency and the distinction between aggression and self-defense, we can offer an anti-war perspective that is passionately pro-peace yet intellectually honest. We don't glorify anyone's war, but we also refuse to pretend that a world in which good people do nothing to stop evil is a peaceful or desirable one.

Let us therefore reclaim the narrative: libertarians are the fiercest opponents of war because we refuse to blur moral lines. We know that only by clearly identifying and condemning aggression, whether by our government or another, can we ever hope to reduce and eliminate war. We don't "see no difference" between sides; we see the crucial difference between violating rights and defending them. In doing so, we uphold the very core of libertarian ethics. If our rhetoric has been hijacked in places by a well-meaning but misguided pacifism that treats war as a mere disaster to manage, we must correct that. This methodological inconsistency leads to moral confusion/ War is a disaster. caused by specific actions of specific people.

Stop those people, and you stop the war.

Ultimately, our vision is a world where all conflicts are resolved without violence. To get there, we need moral clarity in the here and now. That means supporting the innocent individual against the aggressor individual, every time, at every level. Peace and liberty thrive when justice is done, and justice demands we never equate the aggressor and the defender. By avoiding that internal contradiction, libertarians can provide a consistently principled, compelling anti-war voice that truly advances the cause of peace grounded in freedom and responsibility.

Bibliography

[1] "Financial Crises: Keynesian and Austrian School Perspectives." Tutor2u. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/financial-crises-keynesian-and-austrian-school-perspectives

[2] "A Libertarian Theory of War." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-daily/libertarian-theory-war

[3] "Peace and Pacifism." Libertarianism.org. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.libertarianism.org/topics/peace-and-pacifism

[4] "The Non-Aggression Principle." Dialnet. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7097352.pdf

[5] Rothbard, Murray N. "War, Peace, and the State." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/library/war-peace-and-state

[6] "Individualism, Methodological: A Libertarianism.org Guide." Libertarianism.org. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.libertarianism.org/topics/individualism-methodological

[7] "The Keynesian Multiplier Concept Ignores Crucial Opportunity Costs." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/quarterly-journal-austrian-economics/keynesian-multiplier-concept-ignores-crucial-opportunity-costs

[8] "The Austrian School of Economics — Action as an expression of value." ehsto. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://ehsto.com/blogs/undertone-journal/the-school-of-austrian-economics

[9] Horton, Scott. Provoked: How Washington Started the New Cold War with Russia and the Catastrophe in Ukraine. Austin: Libertarian Institute, 2023.

[10] "Lessons Learned: Ron Paul's Warnings Against the War on Terror Stand True." Libertarian Party. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://lp.org/lessons-learned-ron-pauls-warnings-against-the-war-on-terror-stand-true/

[11] Antiwar.com. Accessed May 29, 2025.

https://www.antiwar.com/

[12] Shoenfeld, Joshua. "The Final Solution of Gaza is Imminent." LewRockwell.com. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.lewrockwell.com/lrc-blog/the-final-solution-of-gaza-is-imminent/

[13] "Is It Just War or Unjustified Slaughter of Innocents?" Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-wire/it-just-war-or-unjustified-slaughter-innocents

[14] "War & Foreign Policy: A Libertarianism.org Guide." Libertarianism.org. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.libertarianism.org/topics/war-foreign-policy

[15] Kinsella, Stephan. "Dialogical Estoppel: Erga Omnes Rights and the Libertarian Theory of Punishment and Self-Defense." Journal of Libertarian Studies. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://jls.mises.org/api/v1/articles/73686-dialogical-estoppel-erga-omnes-rights-and-the-libertarian-theory-of-punishment-and-self-defense.pdf

[16] Block, Walter E., and Alan Futerman. "Rejoinder to Gordon and Njoya on Israel and Libertarianism." MEST Journal. July 2024. https://www.meste.org/mest/MEST_Najava/XXIV_Block_Futerman.pdf

[17] Palmer, Tom G. "Something Is Rotting at the Periphery of the Libertarian Movement." Tom G. Palmer Blog. December 11, 2004. http://tomgpalmer.com/2004/12/11/something-is-rotting-at-the-periphery-of-the-libertarian-movement/

[18] Mises, Ludwig von. Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951.

[19] Block, Walter E. "ANTI-WAR? A rejoinder to Antiwar.com, Lew Rockwell, Tom DiLorenzo, and the Mises Caucus of the Libertarian Party." ResearchGate. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382414653_ANTI-WAR_A_rejoinder_to_Antiwarcom_Lew_Rockwell_Tom_DiLorenzo_and_the_Mises_Caucus_of_the_Libertarian_Party

[20] Block, Walter. Interview in Savvy Street. November 2023. https://www.thesavvystreet.com/transcript-in-defense-of-israel-part-ii-walter-block-and-alan-futerman/

[21] Block, Walter E. "The Human Body Shield." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://cdn.mises.org/22_1_30.pdf

[22] Hoppe, Hans-Hermann. "An Open Letter to Walter E. Block." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-wire/open-letter-walter-e-block

[23] Mises, Ludwig von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949.

[24] Mises, Ludwig von. Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1944. Online Library of Liberty. https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/greaves-omnipotent-government-the-rise-of-the-total-state-and-total-war

[25] Hayek, F. A. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944.

[26] "Why Mises (and not Hayek)?" Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-daily/why-mises-and-not-hayek

[27] "The Cycle of Violence in Anti-War Rhetoric." Biblioteka Nauki. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/58661435.pdf

[28] "Rothbard's Theory of International Relations and the State." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-wire/rothbards-theory-international-relations-and-state

[29] "Just War." Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-daily/just-war

[30] "Can a Principled Libertarian Go to War?" Mises Institute. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://mises.org/mises-daily/can-principled-libertarian-go-war

[31] Harris, S. (2014, July 21). The sin of moral equivalence. https://www.samharris.org/blog/the-sin-of-moral-equivalence

[32] F.A. Hayek, "Personal Recollections of Keynes and the 'Keynesian Revolution,'" in The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek, ed. Bruce Caldwell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[33] "Voluntaryism and War," The Voluntaryist Association, April 15, 2025, https://vassociation.com/2025/04/15/voluntaryism-and-war/.

Thank you for another great article! For my part, I'd like to share with you interesting inroads to libertarian theory of war from Ukrainian libertarian thinker, Volodymyr Zolotorov, in his foreword to the Ukrainian edition of Hoppe’s “The Myth of National Defense" translated into English https://medium.com/@vzolotorov/state-national-defense-russia-ukraine-war-and-libertarianism-94359a13b9ca You might find this interesting and in line with your your criticism of libertarian pacifism.

In recent decades, there has been a noticeable shift in some areas of social science and international law toward methodological statism or holism. This perspective focuses on states or institutions as primary units of analysis, often sidelining individual agency. For instance, in international law scholarship, there's a prevalent trend of emphasizing state actions over individual practices, leading to a form of methodological statism .

plato.stanford.edu

+2

journals.law.harvard.edu

+2

yumpu.com

+2

This shift can result in analyses that prioritize large-scale data—such as casualty statistics or economic indicators—over the nuanced motivations and actions of individuals. While such aggregate data provide valuable insights, an overreliance on them may obscure the underlying individual behaviors that drive social phenomena.

en.wikipedia.org

+2

plato.stanford.edu

+2

researchgate.net

+2

Reevaluating Methodological Individualism

Critics argue that methodological individualism has been conflated with reductionism, leading to its diminished application. However, scholars like Francesco Di Iorio advocate for a non-reductionist variant of methodological individualism. This approach recognizes the complexity of social systems and the interplay between individual actions and structural constraints, without reducing social phenomena solely to individual components .

duncanlaw.wordpress.com

+2

academia.edu

+2

researchgate.net

+2

Reengaging with methodological individualism can enrich our understanding of social dynamics by highlighting how individual actions contribute to larger social patterns. Balancing individual-level analyses with aggregate data ensures a more comprehensive approach to studying social phenomena.

If you're interested in exploring this topic further, I can recommend specific readings or discuss how methodological individualism applies to particular areas of social science.

Sources