The Problem With Netflix's 'Adolescence' (2025)

A show about manipulation that falls for Its own tricks

[Careful: Spoilers ahead!]

Netflix’s Adolescence (2025) portrays the recent surge in male teen violence as a byproduct of TikTok trends and “manosphere” online culture. This framing is misleading, because it implies that young men’s violence is a novel phenomenon spawned by social media. In reality, male youth violence has deep historical roots and has waxed and waned across decades – long before the internet. Sociological evidence also shows a recurring pattern: whenever society faces youth delinquency or aggression, there’s a temptation to blame the newest media or subculture. Here, I attempt to gather historical and sociological data to challenge the show’s premise and to demonstrate that male adolescent violence is not new, and that blaming TikTok or YouTube follows a familiar cycle of moral panic. All assertions are supported by longitudinal data, historical examples, and expert analyses, as detailed below.

Long-Term Trends in Male Youth Violence

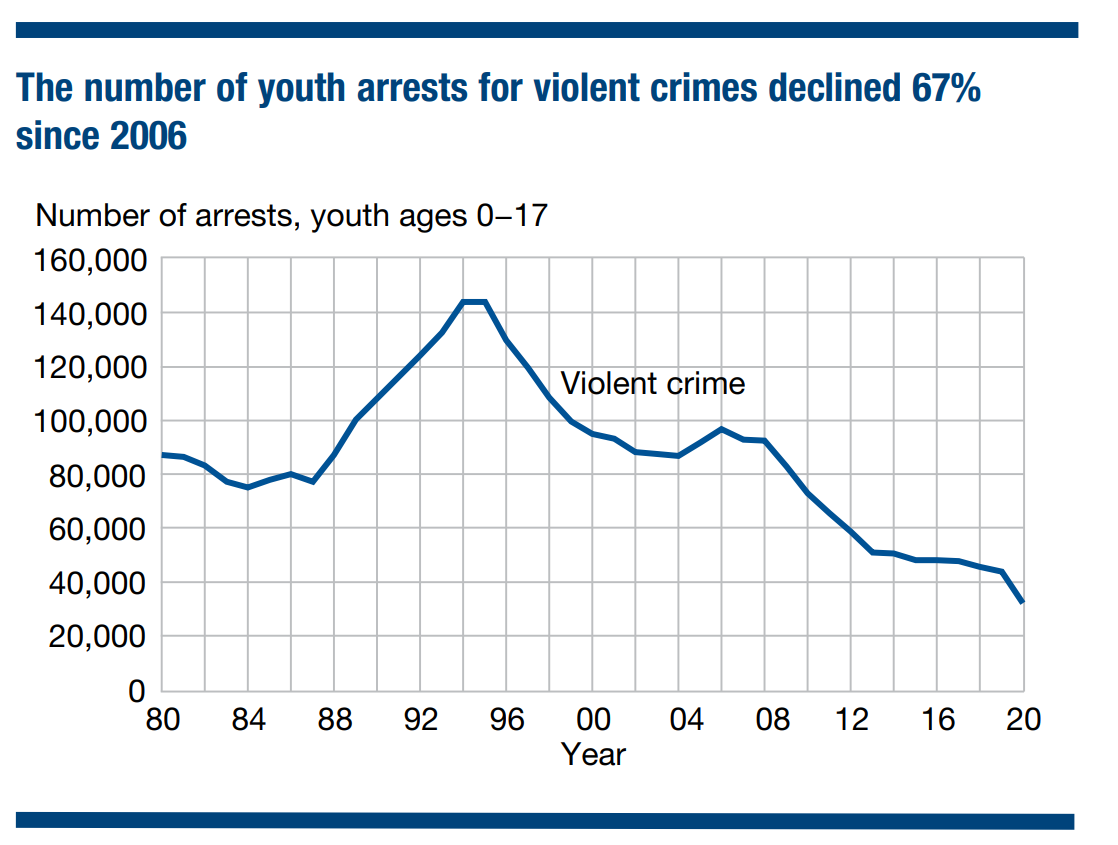

Historical crime data clearly show that violence committed by young males is not unique to the social media era. In fact, youth violence rates have fluctuated significantly over the past century due to various social factors – often peaking long before online platforms existed. For example, in the United States the homicide rate among teen males soared in the late 1980s and early 1990s during the crack cocaine and gang crisis (Youth violence in the United States. Major trends, risk factors, and prevention approaches - PubMed). Between 1985 and 1991, the homicide rate for 15–19 year-old youths jumped by 154%, reaching historically high levels by the early ’90s. This surge predated mainstream internet use. FBI and CDC data confirm that teen violence peaked around 1993 and then declined for many years (Teens 3 times more likely to be killed in 2020-2021 than in 1960: study | Fox News). Figure 1 illustrates this trajectory: after spiking in the ’90s, youth homicide rates fell to lows in the 2000s, and only in the late 2010s have they risen again (partly due to broader societal stresses, e.g. the COVID-era crime uptick). Crucially, even today’s levels remain below the 1990s peak (Teens 3 times more likely to be killed in 2020-2021 than in 1960: study | Fox News). In short, longitudinal evidence shows that male teen violence has existed for generations and tends to ebb and flow in response to social conditions, not simply the latest app or website.

Figure 1: U.S. homicide victimization rate for children/teens (ages 0–19) from the 1980s to 2020. The rate surged to a peak in the early 1990s and then fell dramatically.

(Trends in Youth Arrests for Violent Crimes )

These trends are not confined to one country. In many Western nations, youth violence was a concern well before the digital age. Historian Andrew Davies notes that as far back as the late 19th century, cities like Manchester, UK were “gripped by recurring panics over youth gangs and knife-crime” (Scuttlers: gangs and knife crime - Band on the Wall). During the 1880s, large teenage gangs (known as “scuttlers”) fought turf battles with blades and improvised weapons, terrorizing neighborhoods. A Manchester judge in 1887 lamented that in some districts “life…is as unsafe and uncertain as it is amongst a race of savages,” after jailing a 19-year-old gang member for killing a rival. This Victorian-era panic over youth violence underscores that adolescent aggression is hardly a 21st-century invention – it was making headlines over 140 years ago.

Moving to the mid-20th century, the 1950s saw a notable wave of teenage delinquency and violence in America. Postwar demographics created a booming teen population, and crime by youths drew intense public anxiety. In fact, “the number of crimes committed by teenagers increased by a drastic 45% between 1950 and 1955,” according to a 1955 report in the Saturday Evening Post. This era witnessed the rise of violent teen gangs (the archetype of the leather-clad, switchblade-toting “juvenile delinquent”), as well as notorious individual cases. One infamous example was Charles Starkweather, a 19-year-old from Nebraska who went on a grisly murder spree in 1958, killing 11 people alongside his teenage girlfriend. Starkweather’s case shattered the assumption that extreme youth violence was limited to urban gang members – here was a working-class white teenager from the heartland carrying out random murders, striking fear across America. By 1960, juvenile crime had become one of the nation’s top perceived problems, ranked in opinion polls just behind the Cold War and nuclear threat. Clearly, alienated and violent youth were already a fixture of society’s worries in the 1950s–60s, long before digital media.

Fast forward to the 1980s and 1990s, and we find another surge of teenage violence, again predating social media. U.S. violent crime data show that youths in the late ’80s became more violent even as older offenders did not. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that while overall crime was falling in the early ’90s, murders by 14–17-year-olds jumped 22% from 1990 to 1994 (TRENDS IN JUVENILE VIOLENCE). Over the decade 1985–1994, the homicide offending rate for teens (14–17) “exploded” – increasing by 172%, far outpacing any adult crime increase. Young male gangs armed with newly plentiful handguns drove much of this wave: since 1984, the number of juveniles killing with a gun quadrupled (whereas juvenile murders with other weapons stayed flat). The mid-’90s then saw a steep drop in youth violence – by the year 2000, youth violent crime arrest rates had plummeted almost 80% from the 1994 peak (Trends in Youth Arrests for Violent Crimes ). It’s noteworthy that the worst years of youth violence (late ’80s–’90s) occurred before social networks, smartphones, or even widespread home internet. The deadliest school shootings also began before the age of TikTok: for instance, the Columbine High School massacre in 1999 was perpetrated by two alienated students in an era of dial-up internet (Video Games, Moral Panic, and Scapegoats Through the Years - Take This). Even in the 1970s–1980s, there were incidents of teen-perpetrated school violence (a well-known early case is the 1979 San Diego school shooting by a 16-year-old girl who infamously said she did it because “I don’t like Mondays”). The pattern is consistent: teen violence periodically spikes due to social ills (gang wars, drug epidemics, etc.), not because of the latest communication medium. Today’s fears about TikTok must be measured against this historical baseline. As the Council on Criminal Justice recently found, “homicide rates for teenagers peaked in the early to mid-1990s” and current rates, while elevated compared to the 1960s, are “still below those peaks of the ’80s and ’90s” (Teens 3 times more likely to be killed in 2020-2021 than in 1960: study | Fox News). In other words, blaming a “new” cause like social media for youth violence ignores the fact that even higher levels of youth violence were recorded decades ago – under very different technological conditions.

Furthermore, violence by young males has been a persistent fraction of overall crime. Criminologists have long observed that serious violence (e.g. homicide) is disproportionately committed by young men across eras. Even in recent data, males account for the vast majority of violent youth offenses. For example, in 2020 in the U.S., males made up 92% of all arrests of juveniles for murder (Trends in Youth Arrests for Violent Crimes ). This overrepresentation has held true historically, reflecting underlying social and biological factors in male aggression that transcend any one platform or trend. In short, the inclination toward violence among a small subset of adolescent males is nothing new – statistically and historically, it has always been present. What changes is the broader environment (availability of guns, gang influence, economic stress, etc.) that can amplify or suppress those behaviors. Any claim that today’s male violence is an unprecedented product of TikTok overlooks this well-documented continuity.

Historical Episodes of Teenage Alienation and Violence (Pre-Internet)

To further underscore that troubled, violent youth are not a novelty of the internet age, it’s helpful to look at specific historical episodes of teenage alienation and rage:

Late 19th Century “Scuttlers” (England): As noted earlier, in 1870s–1890s Manchester, teenage street gangs waged violent turf wars (Scuttlers: gangs and knife crime - Band on the Wall). These scuttlers, some as young as 14 or 15, armed themselves with knives, belts, and brute force. The gang clashes were so vicious that local hospitals routinely treated “dozens of [stab] woundings per month” from youth gang fights. Media of the day (newspapers and pamphlets) sounded the alarm about youth running wild. This can be seen as a Victorian precursor to modern teen gang crises – obviously happening long before any digital influence.

1950s Youth Gang Wars (USA): In American cities during the 1940s–50s, youth gangs (often along ethnic lines) were involved in rumbles, knife fights, and occasional shootings. New York City, for instance, had well-known teen gangs like the Fordham Baldies and the Dragons clashing in the streets – events later mythologized in films like West Side Story. The popularity of the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle (about violent, rebellious high schoolers) also reflected real fears of classroom violence and youth out of control. By the late ’50s, concern over teen violence and alienation was so acute that Congress held hearings on juvenile delinquency, and public opinion ranked it as a top concern. This era’s delinquency panic shows parallels to today: adults were perplexed by the “new generation” and some blamed new media (more on that below). Yet clearly the baby boom teens did not need the internet to get into trouble – the anger and alienation of some young men in that era found other outlets, from drag-racing and gang fights to the rock-and-roll youth culture that shocked their elders.

High School Attacks in the 1970s–1990s: While Columbine (1999) is often cited as a watershed, it was not the first instance of teens committing lethal violence at school. In the 1980s and early ’90s, a number of school shootings and mass violence by youth occurred. For example, in 1985, a 14-year-old killed a teacher and wounded several students in Goddard, Kansas; in 1988, an honor student in Winnetka, Illinois set fires and shot children in an elementary school (though most victims survived); and in 1998–1999 there was a string of deadly school shootings in Kentucky, Arkansas, Oregon, and ultimately Colorado (Columbine). None of these perpetrators were influenced by TikTok (which didn’t exist) – their grievances stemmed from personal and social problems (bullying, mental illness, a desire for infamy, etc.). Notably, the media and politicians at the time struggled to explain this violence and often turned to scapegoats like violent video games or music, which we will examine next. The key point is that alienated youth committing horrific acts is not a “Gen-Z” invention – it tragically occurred throughout the late 20th century. If anything, many metrics of youth violence were significantly worse in the past (the early ’90s) than in the TikTok era (Teens 3 times more likely to be killed in 2020-2021 than in 1960: study | Fox News).

Global Perspectives: Outside the U.S., we also find historical examples. In the 1960s, for instance, the UK saw Mods vs. Rockers beach riots – essentially brawls between youth subcultures that caused public panic about youth violence. Earlier, in 1940s–50s Japan, the sun tribe (Taiyōzoku) youths were infamous for reckless, sometimes violent behavior, reflecting postwar social malaise. And looking back further, even in 18th-century Europe there were reports of marauding youth gangs in cities (the word “hooligan” itself arose from youth gang activity in 1890s London). The consistent through-line is that disaffected young males have, in every era, been prone to outbursts of violence, whether through gang activity, schoolyard aggression, or other channels. It is not a phenomenon born in the age of Instagram – it is a long-standing sociological challenge.

In summary, male adolescent violence has ample precedent in history. The internet may amplify or reshape certain behaviors, but it did not create youth violence. Before TikTok, we had violent greasers and skinheads; before YouTube, we had gang members and school shooters influenced by analog frustrations. Any serious analysis of teen violence must therefore avoid the myopic view that it’s an unprecedented “new problem” caused by social networks. As the historical cases above illustrate, today’s violent male youth are walking a trail blazed by many predecessors.

The Recurring Search for Scapegoats

Hand-in-hand with each wave of youth violence comes a familiar societal reaction: moral panic. Rather than confront complex root causes (family dysfunction, social inequality, mental health issues, etc.), public discourse often gravitates toward blaming an external cultural factor – especially new or misunderstood forms of media that adults suspect are “corrupting” the youth. The panic follows a pattern: a new entertainment or youth fad gains popularity; some youth misbehavior occurs; commentators draw a causal link, asserting that “X is poisoning our kids’ minds.” This has happened over and over for decades, long before the online manosphere became a concern. Table 1 below highlights some of the most well-documented moral panics in which media or pop culture were blamed for youth deviance or violence:

Notable Moral Panics Blaming Youth Violence on Media/Pop Culture

Era / Context Youth Behavior Concern Scapegoated Media or Subculture":

1950s: Rise in juvenile delinquency (US) Teen crime wave, gang violence, rebellious youth culture Comic books and horror comics (accused of causing crime) (Video Games, Moral Panic, and Scapegoats Through the Years - Take This); Rock & Roll music (feared to incite unruliness and sexuality); Violent movies (e.g. Blackboard Jungle)

1970s–80s: Occult fears and teen suicides (US) Isolated cases of teen suicide, rumored cult behavior Dungeons & Dragons (tabletop RPG) – alleged to promote Satanism and self-harm (e.g. B.A.D.D. campaign claimed D&D “recruited” teens into satanic cults); Heavy metal music (lyrics misinterpreted as satanic/violent)

1980s: Youth crime and aggression; suburban teen deviance Juvenile violent crime, bullying, teen rebellion Heavy Metal and Rock Music – bands like Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne were accused of driving teens to violence or suicide; Rap Music – mid-80s fears that gangsta rap lyrics would incite real violence (prompting MTV to briefly ban rap videos and politicians to condemn the genre); Arcade/Video Games – early games like Death Race (1976) and later Mortal Kombat raised concerns of desensitizing youth to violence (local arcade bans, etc.)

1990s: School shootings, teen murders (US) Incidents like Columbine (1999) and other school violence Marilyn Manson and Shock Rock – the Columbine shooters’ interest in Manson’s music led to a media frenzy blaming the artist for the massacre (claims later proved false). Manson was demonized as a symbol of everything “wrong” with youth, illustrating scapegoating; Violent Video Games – games like Doom and Wolfenstein 3D (which Columbine perpetrators played) were blamed by many for “training” kids to kill, sparking Senate hearings on video game violence in the 1990s.

2000s: Post-Columbine and other youth crimes Ongoing youth violence, juvenile crime rates Rap and Hip-Hop – artists like Eminem were accused of glorifying violence; some court cases bizarrely cited rap lyrics as motivators for teen crime. Also, the “Satanic panic” of the late 80s extended into early 90s with claims that everything from heavy metal to even kids’ cartoons contained subliminal evil influencing youth. 2020s: Fears of online radicalization (global) Extremist ideologies among youth (e.g. misogyny, incel violence), school threats, etc. Social Media and “Manosphere” – platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and forums are accused of brainwashing young males into violence. E.g. politicians claim TikTok “distorts the world view” of Gen-Z or even “brainwashes” them. Tragic crimes by self-identified “incels” or radicalized teens lead many to blame YouTube algorithms, Twitter, or online gaming chats as direct causes.

As the data suggests, each generation finds a new “villain” in the media to hold responsible for youth misbehavior. In the 1950s, it was comic books and Elvis’s hip-shaking rock music that were supposedly degrading kids’ morals. The U.S. Senate even held hearings in 1954 on whether violent comic books were spawning juvenile delinquents – a classic moral panic that led to comic book censorship (the Comics Code Authority). Churches held bonfires to burn “immoral” comics. At the same time, cities like Memphis banned rock concerts for fear that the music provoked teen violence or rioting. Looking back, these fears seem overblown – comic books and rock & roll did not create a generation of criminals. But at the time, the link was strongly believed by many.

In the 1980s, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) became a surprising target. After a few highly publicized teen suicides and runaways, panicked parents (often spurred by sensational media coverage) claimed the fantasy role-playing game led kids to devil worship or mental instability. A group called B.A.D.D. (Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons) appeared on talk shows insisting D&D was causing real-life violence and occult behavior. This culminated in what scholars call a “moral panic” – extensive fear based on anecdotes rather than data. By the early ’90s, studies debunked these claims, finding no link between D&D and harm. But by then, a new scapegoat had emerged: violent music. As hip-hop and heavy metal gained popularity, they too were blamed for inciting youth violence. In 1988, for instance, the FBI notoriously sent a warning letter to N.W.A. over the song “F** tha Police,”* reflecting fears that rap was fueling anti-authority violence. Politicians like Bob Dole and Tipper Gore lambasted rap and metal lyrics in the ’90s, and some stores pulled heavy metal albums after suicides were (wrongly) linked to bands like Judas Priest. Marilyn Manson became “Public Enemy #1” in the wake of the 1999 Columbine shooting when rumors spread that the shooters loved his shock-rock music . Manson faced record burnings and concert cancellations as panicked communities conflated his stage persona with the causes of school murder. He pointed out the absurdity of the scapegoating – noting that millions of other fans listened to his songs without turning violent – but the moral panic drowned out those nuances. Similarly, video games have been a perennial suspect: from the arcade game Death Race in 1976 (which led to headlines about “video game murder”) to Mortal Kombat (1992) and Grand Theft Auto (2000s), many politicians reflexively linked games to real aggression. Yet, comprehensive research has not found evidence that playing violent games causes violent criminal behavior in youth.

This historical cycle shows that blaming youth violence on pop culture is a knee-jerk response – one that often “misplaces blame in dangerous ways,” as one analyst writes. Indeed, “historically, society has misplaced blame” on new media for youth deviance when in fact those media were usually symptoms or side hobbies of already troubled youth. As early as the 1940s, pinball machines were outlawed in some cities (like New York) as a supposed cause of juvenile delinquency. Going even further back, when the printing press was invented, some feared it would corrupt people’s minds! Each of these panics in retrospect appears to be moral hysteria – an outsized reaction without empirical basis. Social scientists note that moral panics often have “folk devils” – scapegoats like music, games, or now social media, onto which society projects its fears of youth gone bad.

Today’s Fears of Online Radicalization Simply Echo the Past

The current anxiety about TikTok challenges, YouTube radicalization, or misogynistic forums turning young men violent is in many ways a modern replay of these older patterns. To be sure, the internet has novel features – scale, speed, and algorithms – that can facilitate the spread of extreme content. But experts caution that the narrative being pushed (that online content is directly creating violent young men out of nowhere) is strikingly similar to past exaggerations about media’s power. As one technology policy analyst observes, social media today is undergoing a “moral panic” much like previous new media such as TV and radio did (Challenging the Social Media Moral Panic: Preserving Free Expression under Hypertransparency | Cato Institute). He notes that fundamentally, “the kinds of human activities that are coordinated through social media, good as well as bad, have always existed” – what’s different is that they are now more visible. The transparency of online platforms leads people to blame the platform itself for behaviors that were previously hidden. “Internet platforms, like earlier new media technologies such as TV and radio, now stand accused of a stunning array of evils,” from corrupting youth to destroying democracy. This reflex – to attribute causation to the medium – mirrors the old “hypodermic needle” theory of media: the long-debunked idea that audiences are passive and media can “inject” any idea into their minds with uniform effect (A Century-Old, Debunked Theory Is Fueling the TikTok Moral Panic). A recent Vice investigation explicitly draws the parallel between today’s TikTok panic and this “century-old, long debunked theory” of all-powerful media. In the TikTok case, commentators saw a few teenagers posting about a controversial letter (Osama bin Laden’s 2002 manifesto) and jumped to apocalyptic conclusions – that an entire generation was being radicalized en masse by a Chinese app. In reality, researchers found fewer than 50 such TikTok videos, with relatively minor reach. The idea of brainwashing was more viral than any actual brainwashing content. The Vice article concludes that we are in “the fevered depths of a TikTok moral panic” fueled by old assumptions about media’s influence, combined with geopolitical fear-mongering.

None of this is to say that online influences on youth are not worthy of concern. The internet has enabled new subcultures (e.g. incels, white supremacists, etc.) to find each other and potentially reinforce negative worldviews. But the key is perspective and evidence. We must ask: are online forums creating violent impulses, or mainly amplifying grievances that already existed in some boys? Research in criminology and psychology over decades suggests the latter – that young men who become violent typically have a history of personal trauma, social rejection, mental health issues, or exposure to violence in real life. These root causes predate the internet and remain the primary drivers. Online content might act as an accelerant in a minority of cases (just as extremist pamphlets or violent films might have in earlier eras), but it’s rarely the root cause. In fact, some experts warn that focusing too much on the internet as a culprit can distract from tackling deeper issues. For example, Marilyn Manson, reflecting on being scapegoated for Columbine, pointed out that by demonizing artists like him, society was “only further alienating kids who felt marginalized” – essentially, shooting the messenger (Video Games, Moral Panic, and Scapegoats Through the Years - Take This). Likewise, vilifying social media may alienate the very youth we need to engage and help.

Social scientists urge a nuanced approach: recognize that “calls for banning or regulating new media” often recur in history and seldom solve the underlying problem. Instead, a better strategy is to address the known risk factors for youth violence (such as family environment, education, access to mental health care, economic opportunities, and yes, access to firearms in societies like the U.S.). These factors have been identified in studies regardless of era (Youth violence in the United States. Major trends, risk factors, and prevention approaches - PubMed). As one CDC researcher summarized, adolescent violence correlates with things like “early aggression, exposure to violence, poor parenting, negative peer influence, and access to firearms” – none of which are exclusive to the internet. By comparison, the role of media (be it rap music or Reddit forums) is much less direct and harder to isolate.

In understanding the Manosphere (online male-centric communities, some of which promote misogyny or violence), it’s useful to remember previous offline subcultures that were feared: from punk rock gangs in the 1970s to militant cults in the 1990s. The internet can make fringe ideas more visible, but it doesn’t mean every troubled teen is an empty vessel being programmed by YouTube. Teens today, as always, have agency and varied influences. Many consume edgy or controversial content without becoming violent – just as past generations listened to gangster rap or watched horror films without committing crimes. The danger is typically when a youth’s offline life is filled with pain or isolation; then he might seek out extreme online echo chambers that validate violent fantasies. But that is a feedback loop, not a simple cause-effect. Modern fears about online radicalization, therefore, should be tempered with the knowledge that we have been down this road before. As the Cato Institute’s Milton Mueller writes, society often “displace[s] the responsibility for societal acts from the perpetrators to the platform” during moral panics. It’s easier to blame an app than to face complex social failings. Yet, doing so can lead to misguided policies (censorship, overbroad crackdowns) while ignoring real interventions that help youth.

The Issue of the Tates

While the Tates are controversial and complex, the mention of Andrew Tate by name in the show amounts, in my view, to outright defamation and demonization.

There’s plenty to criticize about the Tate brothers—I’ve done so myself on many occasions—but bluntly linking them to murder is both irresponsible and grossly unfair.

Broadly speaking, the "Tate movement" promotes many ideas. But if you boil it down, its core message sounds something like this:

Stop buying into a culture of victimhood and endless emotional oversharing.

You're a man—start acting like one.

Build yourself financially and get in shape.

Respect women, but stop worshipping them.

Quit porn, get off your screens, and take responsibility for your life.

That message, in and of itself, doesn’t drive anyone to kill.

But it does clash directly with the progressive-woke narrative, which holds a very different view of gender and roles.

Take, for example, this viral video by Tristan Tate, viewed tens of millions:

The irony is striking. In the video, Tate gives advice that directly contradicts what we see in the show.

While the killer in the series is obsessive, clingy, resentful, tries to manipulate, and refuses to take responsibility—Tate says the opposite - that the only form of “revenge,” he claims, is to politely walk away, work on yourself, and level up to the point where you're someone others envy.

You couldn’t imagine a clearer contrast between Tate’s message and the behavior of the show's murderer; supposedly a Tate-ian.

The Actual Story

The post wouldn’t be complete without presenting the real story the show is based on.

While they try to convince us there’s a problem with young white men watching too much TikTok—here’s what actually happened in England:

I think that it speaks for itself…

What Should We Make Of It?

Netflix’s Adolescence (2025) presents a clear narrative—teen boy watches toxic content online, becomes consumed with rage, and kills. Viewers are nudged to accept that TikTok masculinity influencers and “incel culture” are not just corrosive, but directly responsible for murder. While the craftsmanship is strong, the message falls into a familiar trap: ideological overreach. The other themes—which are integral to the plot—and the important messages regarding shaming, bullying, parental responsibility, nature vs. nurture, the suffering of the offender's family, minors in the eyes of the law, and the rights of suspects and detainees (such as the break-in into the house), are pushed to the cinematic margins and receive only secondary screen time and importance by comparison.

This is where the show fails. It skips complexity. It doesn’t prove causation—it just assumes it.

Male youth violence is not new. It didn’t begin with smartphones or Andrew Tate. From 19th-century gangs to mid-century juvenile delinquency to the Columbine massacre, history is filled with examples of young men acting out violently—long before YouTube, TikTok, or “manosphere” rhetoric existed.

Each generation has blamed its own media—comic books, rap music, video games. Today, it’s the algorithm. But the real causes—alienation, instability, lack of purpose, broken families—remain consistent. Reducing these to a single online influence is not just wrong. It’s lazy.

Yes, online hate should be taken seriously. Yes, Andrew Tate’s message deserves criticism. But to link a cultural mindset to murder without analysis or nuance is reckless.

If we want a real conversation about masculinity, violence, and youth, we need more than a flashy narrative. We need history. We need context. And we need honesty about what’s really driving boys to break.

Ironically, the show repeats the very kind of ideological move it sets out to critique: It uses a mainstream platform to deliver a message—without dialogue, without reflection, without responsibility .It creates an emotional association between cultural ideas and horrific violence, without testing whether that connection holds .And in doing so, it reinforces exactly what it claims to oppose: A form of storytelling that substitutes emotional pressure and manipulation for critical thought.

Sources

FBI / Bureau of Justice Statistics – Homicide Trends in the U.S.: Age (https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf)

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention – Trends in Juvenile Violence (https://ojjdp.ojp.gov)

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) – Youth Violence in the United States: Major Trends, Risk Factors, and Prevention Approaches (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15583543/)

Band on the Wall – Scuttlers: Gangs and Knife Crime (https://bandonthewall.org/2020/10/scuttlers-gangs-and-knife-crime-in-19th-century-manchester/)

Vice – A Century-Old, Debunked Theory Is Fueling the TikTok Moral Panic (https://www.vice.com/en/article/bvjgmq/the-tiktok-moral-panic)

Cato Institute – Challenging the Social Media Moral Panic: Preserving Free Expression under Hypertransparency (https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/challenging-social-media-moral-panic)

You’ve made an interesting connection between historical influences and media portrayal. It’s true that media can amplify certain narratives, but it also has the power to educate and inspire positive change. Understanding history helps us address root causes and create constructive conversations around youth behavior.

Jacob,

Let’s start with where you’re right—because you are right in places. Your exploration of historical cycles of moral panic is well-documented and clearly researched. Society has repeatedly blamed emerging media for youth violence: comic books, rock & roll, Dungeons & Dragons, rap, video games. Those fears were often rooted more in cultural anxiety than actual causality. You successfully demonstrate how teen aggression and male violence long predate TikTok or YouTube. And yes, moments of societal stress have always made easy scapegoats out of the newest cultural trends. These points are insightful, and they matter.

But where your piece begins to unravel—and ultimately exposes itself—is in what it chooses to ignore, distort, or conveniently sidestep. You claim Netflix’s Adolescence (2025) pushes a simplistic narrative: that teen boys watch Andrew Tate content, become radicalised, and commit murder. But that’s not what the show actually portrays. It examines the ecosystem a vulnerable young man operates within—an ecosystem that doesn’t create violence out of thin air, but amplifies existing wounds. Pain, rejection, loneliness, the need for control. The online manosphere doesn’t invent these things—it exploits them, packages them, and monetises them.

That’s what the show explores. Not a direct cause-and-effect, but an emotional and psychological pipeline. You know this. But you frame the narrative in the most literal, surface-level way to dismiss it more easily. That’s not critique. That’s erasure.

Worse, you mention the real-world case the show is based on—and then sidestep it. You include a single image and a throwaway line: "I think that it speaks for itself..." It doesn't. It demands engagement. A teenage girl was murdered by a boy whose behaviour, mindset, and rhetoric echoed the exact content Adolescence critiques. This isn't theory. It's precedent. And you buried it beneath smug insinuation and an unwillingness to confront the emotional reality of what happened.

This is where your intellectual scaffolding collapses. You cite dozens of articles, academic trends, and media patterns to give the illusion of distance and control. But all you're really doing is protecting a version of masculinity that thrives in abstraction. A masculinity that performs empathy but fears vulnerability. That lifts quotes from discipline culture but never asks who that culture leaves behind.

Then comes your defence of the Tates. You reduce their messaging to neutral, even aspirational soundbites: get fit, take responsibility, don’t worship women. But the Tates don’t operate in a vacuum. Their influence is layered in misogyny, control, and manipulation. You present their message as misunderstood stoicism, but ignore the coercion that often follows it. You cherry-pick the palatable parts and ignore the dangerous whole. You write like someone trying to clean the brand, not critique it.

And it shows. The tone, the posture, the curated detachment. Your article isn't a deep dive. It's reputation management with a bibliography. You say the show manipulates emotion. But so does this article. It selects facts that serve your image, dodges those that don't, and hides behind citations instead of accountability. You don't wrestle with the real implications of manosphere rhetoric on young men—you just defend the parts that make you feel in control. Your version of critique isn't brave. It's safe. And ultimately, it's dishonest.

And let’s be honest—you are that guy. Not maybe. Not hypothetically. You present yourself as the voice of reason, but everything about your writing echoes the very traits you’re trying to excuse. You posture with curated detachment, you lean on borrowed authority instead of personal insight, and you defend ideologies not because they're true, but because they validate a persona you've clearly built: emotionally unavailable, intellectually superior, physically disciplined. The kind of guy who posts gym mirror selfies and sends "checking in" messages to women already spoken for—soft enough to look harmless, calculated enough to keep control.

That tone of restrained charm? The lightly poetic DMs? The rehearsed sincerity designed to position yourself as the emotionally evolved alternative? It’s not subtle. It’s strategy. And maybe ask yourself this—if you believe so strongly in stoic self-improvement and detached discipline... would you send those same sweet, low-risk, high-reward messages to someone in a committed relationship? Would you say it with the same smile if her partner was listening? Or is it just easier to play the thoughtful guy when no one’s watching but you?

The way you write about Adolescence doesn’t just mirror manosphere logic. It is manosphere logic—just cleaned up, cloaked in citations, and dressed in pseudo-critique. The show doesn't preach hysteria. You just couldn't handle its honesty. Because the mirror it held up didn’t reflect a stranger. It reflected you. And instead of facing it, you hid behind a wall of references and wrote it off as a script.

And no, I’m not a bot, and I’m not AI. Just an educated reader who won’t be waving red flags or launching a Substack to rebut you. You’ll likely brush this off like you do anything that doesn’t flatter your sense of command. But the irony? That reaction only proves the point. The one the show made. The one you buried.

Want to keep the discussion going? Or let this stand as the last word? Because as responses go, this one leaves no shadows to hide in.