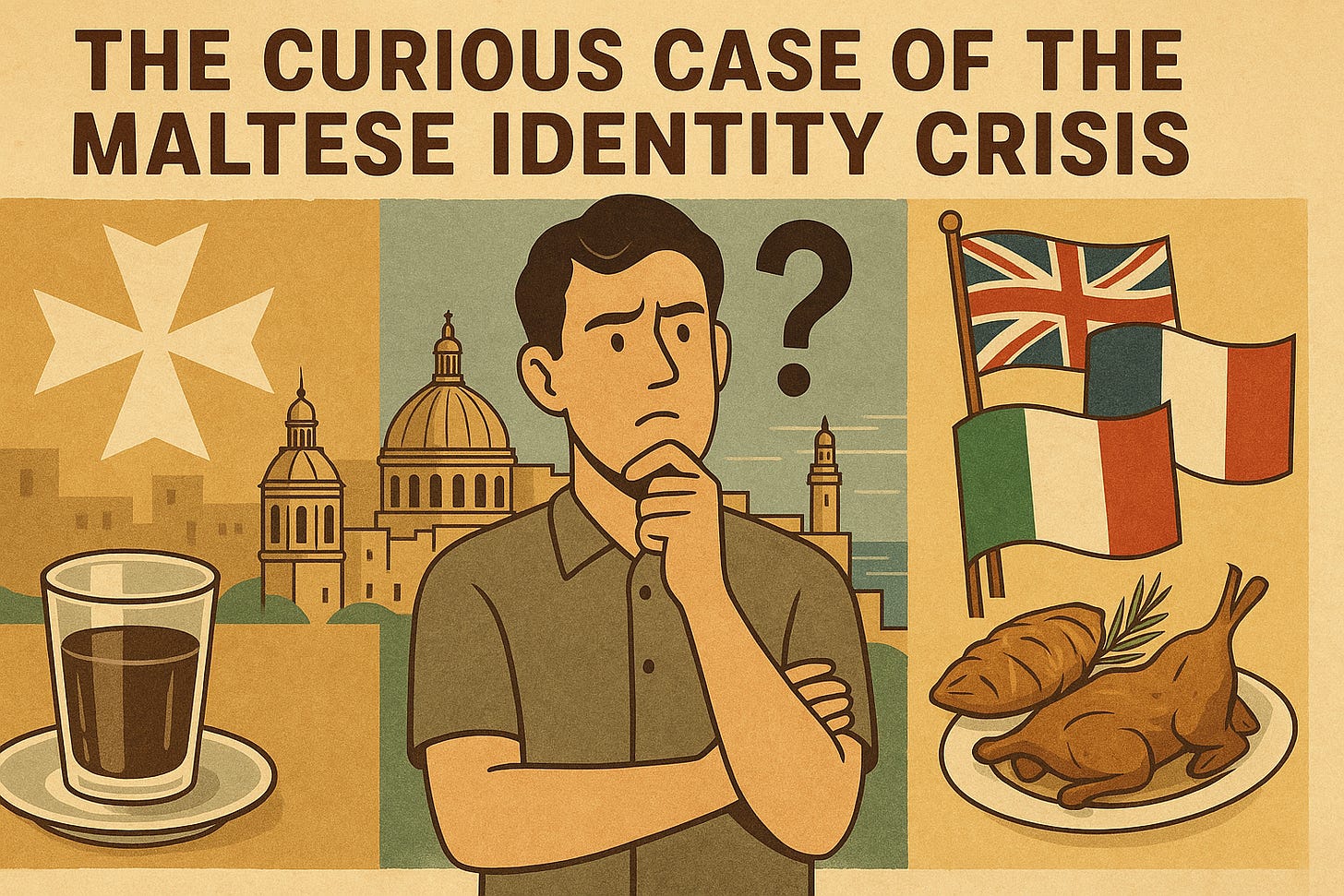

The Curious Case of the Maltese Identity Crisis

When history is deep, but identity feels borrowed

I’m in Malta right now. Beautiful skies, turquoise water, limestone buildings glowing gold at sunset. You’d expect the culture to shine just as bright. But here’s the twist: it doesn’t.

Walk into a café and you’ll likely hear the whirr of an Italian espresso machine, a playlist full of British pop, and a menu offering croissants and cappuccin. But no sign of Maltese tea in a glass, or te fit-tazza. And that sums up the vibe here: ancient island, modern identity confusion.

Pride and Disappearance

Malta has thousands of years of history. A unique language. A rich blend of Mediterranean traditions. And yet, many Maltese today seem more comfortable imitating the English, the Italians, or the French than leaning into their own story.

The stats tell a part of the tale:

96% of Maltese speak English. Many switch languages mid-sentence. Some families speak English exclusively at home. (Languages of Malta - Wikipedia)

86% still say they prefer Maltese, but that doesn’t mean they actually use it in daily life. In work, school, and on social media, English dominates. (Malta - Wikipedia)

Even the national language is getting... streamlined. Dialects are fading. A more anglicized Maltese is emerging.

Meanwhile, Catholicism is still a strong cultural anchor. Over 93% identify as Catholic. Churches are full on Sundays, especially with the older crowd. Religious processions and feast days still pack the streets. This, perhaps, is the one area where Malta expresses identity with confidence. (MaltaToday)

What’s Disappearing?

Folk music like għana (a kind of poetic, improvised singing) is rarely heard outside traditional events.

Crafts like lace-making and silver filigree are now mostly souvenir items made by aging artisans.

Traditional weddings with the old għonnella cloak and village customs? Almost extinct. Western-style receptions have taken over.

Maltese food—rabbit stew, hobż biż-żejt, Kinnie is still here, but often overshadowed by fast food and international chains.

The culture isn’t gone. But it’s hidden. It’s the quiet voice in a room full of louder, glossier influences.

A Small Island in a Loud World

What makes this even more interesting is comparing Malta to other places.

Japan, for instance, is deeply modern yet fiercely protective of its traditions. People still learn calligraphy, wear kimonos, celebrate tea ceremonies. The government honors master artisans as national treasures. You can eat a McDonald’s burger in Tokyo, but you’ll probably sit next to someone quietly reading a manga and sipping green tea. (Culture of Japan - Wikipedia)

Greece is all-in on being Greek. From national parades to schoolkids learning traditional dances to grandmothers reciting folk tales. Even during economic collapse, Greeks doubled down on their culture: cooking more at home, embracing village life, rediscovering the past.

Ireland took things even further. After independence, it revived Gaelic, preserved native sports, and exported its culture worldwide. You can hear Irish fiddle music in New York, Melbourne, or Tokyo. St. Patrick’s Day is global. Ireland made its heritage cool.

Now think of Malta. It has Neolithic temples older than the Pyramids. A language that mixes Arabic structure with Romance vocabulary. And yet… it’s easier to find pizza than fenkata. Easier to hear Italian than traditional Maltese proverbs.

Pride, Shame, and Something in Between

Part of this comes from Malta’s colonial past. British rule, Italian media, EU integration; each layer added a new influence. And while multilingualism and cosmopolitanism are strengths, they can also blur identity.

Some Maltese joke about how “small” or “loud” their country is. Some praise foreign systems and roll their eyes at local ones. This self-deprecating humor isn’t unique, but it hints at something deeper. A quiet insecurity? A cultural cringe?

Still, national shame can be a powerful motivator. In Ireland, it fueled revival. In Japan, post-war humility helped reinvent a global identity. Malta might be next.

Where Malta Could Go

There are signs of hope. Cultural organizations are reintroducing folk music to young people. UNESCO recently recognized Maltese ftira as intangible cultural heritage. People are talking about preservation.

The real challenge is this: can Malta reclaim its voice? not by rejecting the global, but by proudly owning the local. Can it celebrate għana and pastizzi with the same confidence it has for Starbucks and Netflix?

If yes, then maybe the curious case of the Maltese identity crisis won’t be a crisis at all.

Just a turning point.

[The beauty of St. Julian, Malta. Photographer: Yours truly.]

Sources

MaltaToday Survey | Maltese identity still very much rooted in Catholicism — MaltaToday

Malta - Wikipedia — Malta

Languages of Malta - Wikipedia — Languages of Malta

Culture of Japan - Wikipedia — Culture of Japan