Freedom, Authority, and the Logic of Crypto Networks

[Published in the Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2025):

Kohn Faran, Oded Jacob, and Er’el Granot. 2025. “Philosophical Foundations of Cryptocurrency Splits: Freedom, Governance, and Control.” Journal of Libertarian Studies 29 (2): 100–117. https://doi.org/10.35297/001c.151236.]

Throughout history, the struggle between oppression and liberty has been a recurring theme. Yet clashes between differing interpretations of freedom are far less common. In theory, well-defined property rights should naturally align with free-market principles, just as decentralized governance should support, rather than contradict, economic openness. Likewise, individual privacy from government and governmental transparency are both core elements of a free society, seemingly without inherent contradictions.

It is crucial to stress that principles such as decentralization, economic openness, and privacy are not the be-all and end-all of a libertarian society. While they generally improve freedom, they are not always in perfect harmony. A libertarian government may need to be centralized in certain cases to prevent a decentralized unit from infringing on individual liberty. This tension is the very subject of this article. The cryptocurrency ecosystem, acting as a dynamic laboratory, reveals that the implementation of these fundamental values can lead to direct conflicts, forcing communities to choose which aspect of freedom to prioritize.

The cryptocurrency ecosystem, however, arguably the freest financial system ever created, demonstrates that these foundational aspects of freedom can sometimes come into direct conflict. In the cryptocurrency ecosystem, network splits (forks) occur when community disagreements become irreconcilable, reflecting not only technological disputes but also deeper social and political values. Each fork highlights how ideological perspectives shape technological decisions.

Blockchain networks function as decentralized financial structures where any modification requires broad consensus (Alden 2023; Ammous 2018). This characteristic slows down changes but ensures long-term stability. But this conservatism generates an inherent tension between four pairs of opposing values that influence the evolution and identity of cryptocurrency networks.

First, there is a tension between value storage and payment functionality. Blockchains in general, and bitcoin in particular, are viewed as systems that ensure stable value preservation over time, similar to gold or other value stores (Antonopoulos 2017, 2022). Here, it is crucial to distinguish between bitcoin’s short-term price volatility and its ideological role as a store of value. While many view bitcoin as a speculative asset due to its price swings, a significant portion of the community holds the belief that its fixed supply serves as a hedge against currency devaluation and inflation. From this perspective, bitcoin is a financial tool for long-term value preservation—similar in principle to gold—despite the practical realities of its price fluctuations.

Many economists agree that money’s function as a store of value is inextricably linked to its being a medium of exchange—more precisely, there is a tension between ease of payment and network security. The bitcoin community often presents this tension as a direct conflict. For example, prominent bitcoin advocates such as Michael Saylor argue that bitcoin is a store of value but not—nor should it be—a day-to-day currency. They differentiate between bitcoin’s property of storing value and its function as a payment network. Bitcoin’s potential as an efficient tool for quick and inexpensive transactions depends on a technological flexibility that allows for market adjustments, and this creates a fundamental tension between viewing blockchain as a stable financial asset versus its use as a daily payment method.

Second, there is a conflict between decentralization and flexibility. Decentralization is a core value in the crypto world, ensuring resistance against centralized control or leadership failures. But decentralization itself limits the ability to implement substantial technological changes and respond quickly to urgent issues. This tension stems from questions about whether and how system flexibility can be incorporated without compromising the network’s decentralized nature.

Of course, one might argue that the ideal monetary layer would be immutable and not require technological changes, since trust in monetary tools often relies on their resilience to change. One of gold’s core strengths, after all, is that its resiliency is unrivaled. But bitcoin is more than just a digital accounting unit; it also functions as a payment layer, and other blockchains include complex smart contracts. Therefore, just as payment methods had to evolve to meet market demands during the gold standard era (e.g., checks and telegraphs), blockchains must be able to adapt to the exponentially growing demands of a digital economy where payments occur on a decentralized network.

Third, there is a struggle between institutional certainty and enlightened censorship. One of blockchain’s key advantages is its inherent certainty—an immutable history providing a reliable foundation for economies and users. In extreme cases, however, questions arise about whether “enlightened censorship” (such as intervention to prevent fraud or recover stolen funds) can be legitimate and not undermine network trust and the principles ensuring its unique character.

To be more specific, traditional, centralized payment systems (such as banks or credit companies) allow transactions to be undone. On the one hand, this feature reassures honest customers that funds can be retrieved in the event of theft or fraud—a clear societal benefit. On the other hand, this same power of intervention means that a transaction is never truly final. The ability of a central authority to reverse or block a payment, even with the best intentions, is a form of censorship over the financial record. This is a core point of contention in the cryptocurrency space, where some communities prioritize an immutable, final ledger over the ability to correct for fraud.

Fourth, we observe a balance between transparency and privacy. Blockchain networks are inherently capable of recording every transaction transparently and immutably, providing absolute transparency. Alongside this transparency, however, is a growing demand from many users for privacy protection, especially in an era where government surveillance and access to user data have become sensitive issues. The tension between these two values significantly shapes the development and philosophy of competing blockchain networks.

The following sections will explore how these struggles manifest within the cryptocurrency realm. Since they revolve around money and control, they are often accompanied by politics, censorship, ego, and propaganda behind the scenes. This article, however, focuses solely on the philosophical foundations of these debates, avoiding an examination of the internal politics and specific events that sparked them. The mere existence of such conflicts within a free society is a novel and fascinating phenomenon that warrants greater attention.

We do not claim that either the blockchain splits themselves or the subsequent market outcomes are solely driven by ideology. Indeed, it is beyond the scope of this article to quantify the degree to which these events were influenced by economic incentives, technical decisions, or market dynamics such as path dependency and brand recognition. Our purpose is to document a unique phenomenon: the ideological disputes that accompanied every major blockchain split. The debates surrounding these conflicts consistently used libertarian principles as their primary framework, each opposing side arguing from a different, yet valid, philosophical stance.

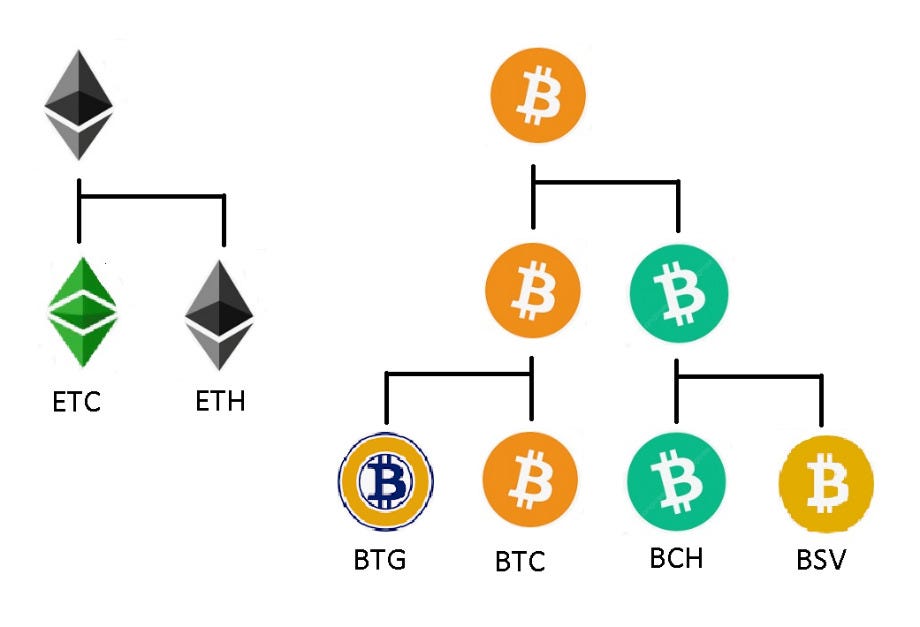

Figure 1.The main splits, or forks, in the ethereum (left) and bitcoin (right) ecosystems

Why Forks Are Always Accompanied by Conflicts

A network split, or fork, is a fundamentally different event from the creation of a new, competing product. The creation of a new, unrelated coin is akin to a company launching a product in a competitive market—consumers are free to choose their preferred option, and there is no inherent conflict within the community. When a blockchain network forks, on the other hand, it is an existential event that affects all participants. As Metcalfe’s law suggests, a network’s value is proportional to the square of its users. Consequently, splitting a payment network immediately results in a significant loss of value for both resulting networks. Moreover, a split introduces substantial technological risks, since it’s unclear how old software and hardware will function in the new environment. Experts often advise users to avoid making transactions in the hours following a fork due to these risks. Furthermore, centralized entities such as exchanges may not support the new coin, leading to a loss of value for their customers.

Because of these grave perils, a network fork is something that all developers and most users actively try to avoid. The costs are typically too high for a community to risk it lightly. Therefore, when a split does eventually occur, it is almost always a result of a genuinely unresolvable conflict—a dispute so fundamental that the community would rather risk the destruction of the network than compromise.

In the following sections, we will analyze the main ideological conflicts that led to the primary blockchain splits. While these decisions may appear at first glance to be ordinary engineering or management choices, we contend that they are unique and have a deep connection to libertarian thought for the following reasons.

First, in every conflict, both sides grounded their arguments in libertarian principles. For example, instead of promoting their coins on the basis of superior technical properties such as affordability or ease of use, they invoked concepts such as empowering the free market, improving decentralization, protecting individual privacy from government surveillance, and enforcing governmental transparency. This represents a significant departure from typical industrial disputes.

Second, the crypto ecosystem—particularly in its early, unregulated stages—provided a unique and priceless opportunity to investigate how a free community decides between different libertarian arguments.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, some of these conflicts were not about quantitative trade-offs (e.g., more versus less transparency, as seen in BSV’s split from BCH). Instead, they involved a choice between two foundational principles that, under normal circumstances, libertarians would consider nonnegotiable. The ethereum–ETC conflict is a prime example: the community was forced to choose between the absolute immutability of a contract and the imperative to protect private property. The fact that a community was compelled to make a choice between these two pillars of freedom is a phenomenon that warrants deeper philosophical analysis.

The Ethereum Network Split—Immutability versus Private Property Protection

Ethereum, launched in July 2015, was created to facilitate the development of decentralized financial applications, eliminating the need for intermediaries such as banks and exchanges (Buterin 2014). It pioneered the use of smart contracts—self-executing code designed to enforce contractual terms automatically, without human intervention or the risk of external manipulation (Szabo 1997; De Filippi and Wright 2018).

In 2016, the DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) emerged as one of the most ambitious and innovative projects on the ethereum blockchain (Siegel 2016). Designed as a decentralized governance model, it operated without a traditional hierarchy, relying on a smart contract as its constitutional framework. Investors contributed funds in exchange for voting rights, allowing them to participate in decision-making. Less than a month after its launch, however, a vulnerability in the smart contract was exploited, enabling an attacker to siphon approximately $50 million of the $150 million invested in the project (Popper 2016; Price 2016).

The DAO was governed by a smart contract, a piece of self-executing code designed to follow a two-step process when investors wanted to withdraw their funds:

Send the requested amount of ether to the person’s account.

Update the person’s balance on the contract to reflect the withdrawal.

A bug in the code, however, allowed a user to trigger the first step repeatedly before the second step (updating the balance) could be completed. An attacker exploited this flaw by writing code that created a loop continuously requesting money. Because the smart contract was busy fulfilling the initial withdrawal request, it never had the chance to update the attacker’s balance to zero. This enabled the hacker to siphon off a significant portion of the DAO’s funds by repeatedly “withdrawing” money that the contract still believed was held. The breach sent shockwaves through the ethereum community, triggering a deep crisis that called into question the network’s core principles and security.

This incident raised two fundamental moral and technological questions. The first concerned whether the exploit constituted theft. One perspective argued that the attacker did not breach the system or violate the contract’s code but instead operated within the parameters it allowed, potentially making the exploit a legitimate application of the contract’s rules. But the majority of the community viewed it as theft, emphasizing that it inflicted harm on users and undermined the project’s intended fairness. This perspective was based on the fact that most investors were not programmers and were therefore unaware of the vulnerability; their expectation was that their money was secure. In judicial terms, the action was seen as inconsistent with the spirit of the contract, and the fact that people were ignorant of a technical flaw did not justify another party’s taking their money.

The second question was whether it was right to intervene and change the blockchain’s history. Ethereum was designed to be an immutable ledger, meaning its records were permanent and unchangeable. This immutability was a core principle, guaranteeing the network’s reliability and decentralization. But reversing the hack to return the stolen funds would directly violate this principle. This created a conflict between upholding the core value of immutability and remedying an injustice caused by the exploit.

The ethereum classic (ETC) community adhered to the principle that code is the ultimate law, rejecting any modifications even in exceptional cases. This stance was based on core principles such as nonintervention—ensuring the blockchain remained resistant to censorship and immutable; code sovereignty—treating smart contracts as binding agreements where investment risks fell on users who failed to identify vulnerabilities; and technological freedom—maintaining nonintervention as an absolute principle of user autonomy, even at the cost of financial loss or reputational damage. Additionally, altering the blockchain was seen as a corrupt practice that benefited individuals closely associated with the Ethereum Foundation.

Conversely, the ethereum (ETH) community prioritized the network’s reputation, fearing that the DAO exploit—by which significant funds were stolen from ethereum’s flagship project—could damage confidence in the ecosystem. While ETH advocates agreed that “code is law” and that smart contracts define property rights, they viewed the DAO hack as evidence of the market’s immaturity in adopting these new legal frameworks. In their view, the blockchain’s existing rules were insufficient to fully protect market participants’ property rights, justifying intervention beyond the blockchain itself.

This approach, supported by the majority of the community (including ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin), emphasized that justice and fairness demanded a reversal of the exploit to correct user harm. This perspective prioritized the community’s responsibility to protect investors from unforeseen vulnerabilities and showed a willingness to compromise on immutability to achieve broader goals, such as restoring confidence in the network.

The split, referred to as a “fork” in cryptocurrency terminology, resulted in the creation of two independent networks (Siegel 2016; Cuen 2017): ethereum (ETH), where the majority chose to reverse the effects of the exploit, and ethereum classic (ETC), where a minority remained committed to the original blockchain principles, rejecting any form of modification or censorship (see the left part of figure 1).

This division underscores a fundamental tension between two competing priorities: strict adherence to blockchain-determined property rights and the imperative to protect users from harm. Both factions uphold the principle of blockchain-based property rights, but their disagreement lies in how to resolve conflicts between internal blockchain rules and broader notions of universal property rights. The ETH community maintains that, in certain circumstances, ensuring universal property rights justifies altering the blockchain’s internal rules.

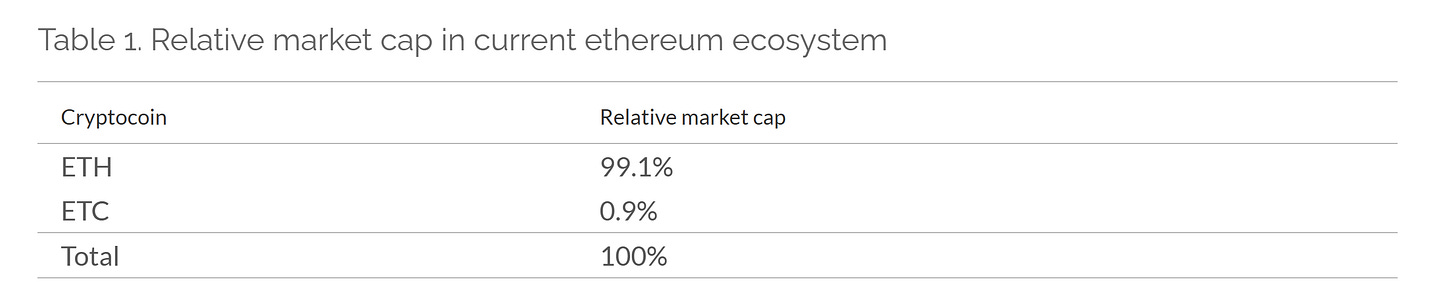

As of this writing, the ETC network represents only about 1 percent of ethereum’s total market capitalization, with its market share continuing to decline (see table 1). This trajectory signals a decisive victory for the ETH community.

Table 1.Relative market cap in current ethereum ecosystem

Source: January 2025 data from CoinMarketCap (n.d.).

Note: Percentages represent the relative share of total market capitalization within the ethereum ecosystem (ETH + ETC).

The Bitcoin Network Split—Decentralization versus Market Flexibility

In 2017, the bitcoin network faced a significant growth crisis. The increasing number of network transactions created a bottleneck, resulting in high fees and exceptionally long transaction confirmation times. Many had already pointed out the network’s scaling issues several years earlier, but by 2017, the problems had become too severe to delay a solution any longer.

The primary dispute centered on how to address this growth. One approach suggested a direct technical solution through increasing the block size to allow more transactions in each block (De Filippi and Wright 2018; Bier 2021). While this would improve short-term network capacity, it raised concerns about long-term effects on network decentralization and security. The alternative approach proposed second-layer solutions, such as the lightning network (Poon and Dryja 2023; Antonopoulos 2022) and liquid network (Vigna 2015; Ver and Patterson 2024), which would move most transactions to secondary networks above the main blockchain while maintaining small block sizes. This controversy extended beyond technical considerations to encompass ideological values—particularly regarding decentralization, flexibility, and free market principles (Popper 2016, 2017; Reiff 2024).

The dispute gave rise to two main ideological camps, each proposing different solutions based on distinct values. Bitcoin core (BTC), led by bitcoin’s original development team, focused on preserving the existing block size. The team’s primary concern was to maintain decentralization by keeping the block size limit at 1 megabyte. They argued that increasing the block size would significantly expand the blockchain’s overall volume, requiring nodes to store more data. This, in turn, could lead to centralization, since smaller nodes running on affordable hardware might struggle to keep up. Additionally, delays in transmitting large blocks across the network could disrupt consensus, potentially causing undesirable network splits.

BTC preferred developing second-layer solutions, such as the lightning and liquid networks, that would enable fast and cheap transactions outside the main chain. This approach maintained a small, manageable main blockchain while addressing high transaction volume needs. They viewed block size limitation as an internal regulation that would prevent powerful entities from controlling the network and thereby prioritize decentralization and network security even at the cost of higher fees and longer transaction settlement times (Popper 2017).

In contrast, bitcoin cash (BCH) was founded on the belief that second-layer solutions were superfluous technological complications. They advocated increasing block size to meet market demand (initially to 8 megabytes), which would allow more transactions per block and reduce congestion and fees. BCH supporters viewed the 1 megabyte limit as an arbitrary restriction preventing the network from reaching its growth potential. They believed market forces, not developer decisions, should determine block size on the basis of demand to promote a more dynamic, market-based, less conservative approach (Popper 2016).

The conflict reached a critical point in mid-2017. To prevent a costly fork, two opposing camps met in New York to forge a compromise known as the New York agreement. The proposed protocol was to activate SegWit, a bitcoin upgrade that would enable second-layer solutions and simultaneously raise the block size from 1 to 2 megabytes. This compromise aimed to satisfy both sides: the small-block camp would get SegWit and the big-block camp would get a block size increase. But the agreement failed to gain the necessary consensus from the wider community. Lacking broad support, many of its initial backers eventually dropped out, and the planned upgrade was ultimately abandoned, making the split inevitable.

The disagreement proved irreconcilable, leading to the August 2017 split into two separate blockchain networks. BTC maintained its focus on decentralization and network security, while BCH pursued network capacity and market-based flexibility (see the first split on the right part of figure 1). This division reflects the ongoing tension in the crypto world between absolute decentralization principles and market demand responsiveness (Reiff 2024).

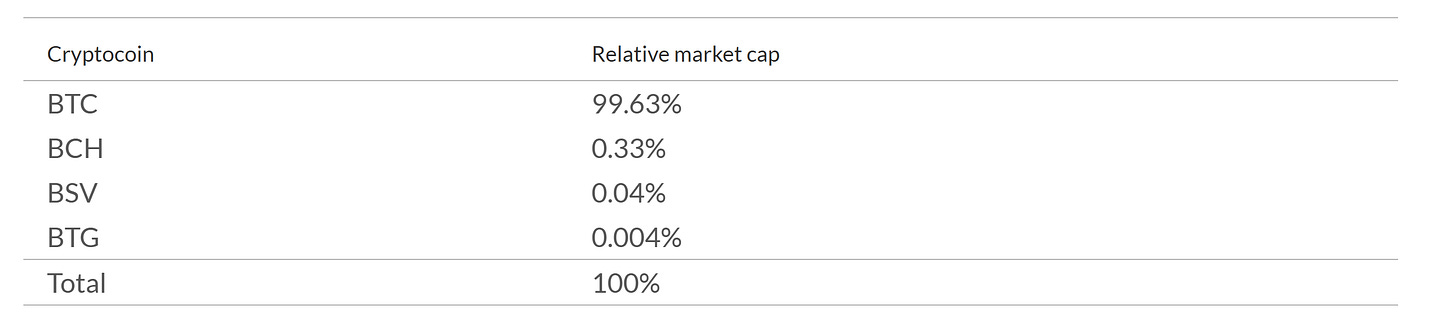

BTC has maintained its position as the leading cryptocurrency, benefiting from strong public trust, robust decentralization, and growing institutional adoption. At the time of writing, the BCH market cap is less than 0.4 percent of that of BTC (see table 2). BTC’s network, however, faces ongoing challenges with scalability, high fees during peak periods, and reliance on external solutions. BCH, while offering faster and cheaper transactions, has struggled to achieve widespread adoption and faces persistent questions about long-term network centralization and security risks.

These divergent paths continue to shape both networks’ development and serve as inspiration for further blockchain innovations. The split demonstrates how different interpretations of freedom—whether as structural decentralization or market flexibility—can lead to fundamentally different technological and economic approaches.

The Bitcoin Cash Split—Privacy versus Transparency

In 2018, approximately one year after the bitcoin split that created bitcoin cash (BCH), this network experienced another significant division stemming from a fundamental ideological dispute. The split emerged from differing approaches to the basic values of privacy and transparency—two competing principles in the cryptographic world.

At the heart of the controversy were two distinct interpretations of freedom. Key advocates within the bitcoin cash (BCH) community prioritized privacy as a means of protecting user rights and shielding individuals from government interference (Bitcoin Cash Podcast, n.d.). In contrast, supporters of bitcoin Satoshi vision (BSV) emphasized complete transparency as a mechanism for public oversight and corruption prevention (Brothwell 2023).

While technical factors, such as block size and network expansion strategies, played a role, the core ideological divide centered on the trade-off between privacy and transparency. But the differences between these networks extended beyond this issue. The BSV community opposed modifications made to the original bitcoin protocol by both the BTC and BCH networks, believing that immutability was essential to maintaining sound money (hence the origin of its name) (Lewis 2024).

To be more specific, the BSV community’s philosophy was to restore what they believed was the original design of bitcoin, not to further modify it. The bitcoin script opcodes that had been disabled or restricted in BTC and BCH were reenabled in BSV to restore the original protocol’s full functionality for more complex applications. In particular, the BSV team opposed the 1 megabyte block size limit, which was added in 2010 as an antispam measure. Proponents of BSV believed this limit was supposed to be a temporary measure and that the original protocol was designed to be a global electronic cash system capable of handling a huge volume of transactions directly on the blockchain. They argued that to compete with traditional payment systems, the block size needs to be essentially unlimited.

BCH maintained that privacy is a fundamental condition for ensuring user freedom, serving as the primary defense against government intervention and political coercion. The BCH network mixed certain mechanisms to obscure transaction data and prevent tracking. BCH wallets offered built-in privacy enhancement functions (for example, the Electron Cash wallet), reflecting a commitment to financial anarchism and the goal of removing governments and banks from the monetary market. According to this perspective, privacy is crucial for a free market where no central entity can monitor or control transactions.

Conversely, the BSV community viewed transparency as a fundamental principle for ensuring public freedom, advocating for an approach that enabled comprehensive tracking of all network activities. To support this vision, BSV significantly increased the block size, allowing all transactions and relevant information to be recorded on the blockchain. This approach aimed at creating a highly inclusive infrastructure where a massive blockchain could encompass worldwide financial activities. With all blockchain activities fully traceable, even governments would be unable to operate without complete transparency (Brothwell 2023). BSV’s philosophy prioritized public transparency over private anonymity, arguing that when all information is openly accessible, governments are compelled to act more fairly and efficiently, driven by the fear of corruption or abuse being exposed.

The split created two ideologically opposed networks, each pursuing a different direction (see the second split of BCH in figure 1). The BCH community continued to advance privacy and market determinacy as central values, developing technological mechanisms to ensure user anonymity. This network maintained support among users who saw privacy as a condition for economic freedom. It focused on creating a free market for daily payments, where government intervention was impossible.

The BSV community focused on developing transparent infrastructures on a large blockchain—including broader applications such as data storage and various institutional uses—aiming to create a completely transparent economic system. It attracted users and entities that valued oversight and control rather than personal privacy.

At the time of writing, the BSV network constitutes only about 10 percent of the BCH market cap (see table 2).

This dispute between BCH and BSV transcends mere technological differences, reflecting deeper ideological and moral considerations about the nature of freedom itself (Bier 2021). BCH’s approach views privacy as a tool for preserving individual liberty and preventing oppression, arguing that true freedom exists only when users have complete control over their personal and financial information. BSV sees transparency as a value protecting society as a whole. It seeks to create mechanisms that ensure fair governance and accountability, thereby prioritizing collective freedom over absolute individual privacy.

These competing visions demonstrate how decentralized technologies serve as a testing ground for fundamental value questions that continue to shape the future of cryptocurrency networks. The tension between individual privacy rights and collective transparency benefits represents a broader societal debate about the balance between personal freedom and public accountability in the digital age.

The Splits Persist

Although the splits mentioned above were the most well-known and had the largest impact, they were by no means the last. Shortly after the BTC–BCH split in 2017, BTC underwent yet another fork. In this case, a group of developers modified the mining algorithm to prevent ASIC mining (an application-specific integrated circuit miner is a hardware device specifically made for mining cryptocurrencies) and allow users to mine with their CPUs and GPUs instead. This change was intended to improve network decentralization, bitcoin mining having become the exclusive domain of experts (Reiff 2023). The resulting cryptocurrency, bitcoin gold (BTG) (see BTC’s second split in figure 1), was largely ignored by the bitcoin community, and as of this writing, its market capitalization remains negligible compared to BTC (~0.005 percent—see table 2).

In late 2018, another split occurred within the BCH network. A team of developers proposed allocating 8 percent of mining rewards to fund development (Popper 2016; Shen 2020). Most of the community, however, viewed this as a form of forced taxation, which contradicted BCH’s anarchic ethos. As a result, the new coin (BCH ABC) was largely rejected by users and miners and is now practically nonexistent.

Clearly, debates over freedom and governance will continue to be a defining feature of the crypto world for a long time to come.

Table 2. Relative market cap in the current bitcoin ecosystem

Source: January 2025 data from CoinMarketCap (n.d.).

Note: Percentages represent the relative share of total market capitalization within the bitcoin ecosystem (BTC + BCH + BSV + BTG).

In the context of decentralized networks, the concept of a winner is not as clear as it is in a centralized world. There is no mechanism to completely eliminate an unsuccessful blockchain as long as its advocates remain committed to it. Furthermore, a definitive analysis of why a particular coin won and how it did so—considering factors such as network effects, miner support, and user adoption—is a vast and complex topic beyond the scope of this article. Our focus remains on the ideological clashes themselves. Nevertheless, the adoption dynamics are so dramatic and powerful that they cannot be ignored, and for completeness, we present the results below.

There are numerous ways to quantify the success of a blockchain fork, including metrics such as the number of active users, the computing power devoted to mining, the volume of transactions, and the level of real-world adoption. But these metrics are all deeply interconnected with a coin’s market capitalization. For instance, the value of a network is not just about the number of its participants but also the wealth they hold. Similarly, the total value transferred over a network is often more important than the raw number of transactions. Ultimately, a coin’s market capitalization serves as the most comprehensive indicator of its overall network value, security, and market confidence; therefore, in our analysis, we will use this metric to evaluate the relative success of each fork.

An analysis of market capitalization in both the bitcoin and ethereum ecosystems reveals dominant networks within each. ETH accounts for over 99.0 percent of ethereum’s total market capitalization, while BTC commands more than 99.6 percent of bitcoin’s market cap, along with the vast majority of its hash power. In contrast, bitcoin cash (BCH), which once held over 20 percent of bitcoin’s market capitalization at its 2017 peak, has declined to less than 0.3 percent today. This shift reflects a decisive market preference. The key question is, Why did these particular options prevail, and what are the broader implications for financial sovereignty, freedom, and decentralization?

The cryptocurrencies that emerged as dominant were not necessarily those that adhered most strictly to the original protocol—otherwise, bitcoin SV would have prevailed. Nor were they the ones that prioritized blockchain immutability, as ETC did. They were not even the versions supported by the original developer teams (e.g., BCH ABC and BCH) or those favored by mining companies (e.g., BCH).

Instead, the dominant cryptocurrency in each ecosystem appears to be the one endorsed by the majority of developers. These developer communities communicate their preferences and rationale through social media, forums, and official publications, shaping public perception and influencing adoption. Once a particular coin gains the most developer and community support, network effects drive further capital inflows, reinforcing its position. At that point, adherence to the “original” vision or even technical superiority becomes secondary to liquidity, ecosystem growth, and widespread adoption.

In the discussion above, we do not claim that the majority of developers’ adoption is the sole reason for a coin’s success. It is an observed fact that in each case, the majority of developers were on the winning side, but this does not diminish the influence of miners, node owners, users, and exchanges. It only suggests that developers’ control over the core code and communication channels is a powerful force. Furthermore, as Popper (2016, 2017) shows, developers who held control over influential websites and bitcoin forums used censorship to suppress rival coins. Sadly, ideological and technical debates often deteriorated into personal attacks. Instead of questioning the technical properties of the new coins (especially BCH and BSV), influencers and ordinary people began attacking the coins’ main advocates, such as Roger Ver for BCH and Craig Wright for BSV. While these are clearly ad hominem attacks, the accusations gained traction, and the resulting bad publicity at least partially affected the new coins’ adoption.

Ultimately, as explained in the first section, the network effect is a powerful force that compels participants to adopt the dominant coin, even if they ideologically favor another. The overwhelming dominance of BTC and ETH over their forks is a complex phenomenon that will require extensive future research to fully understand.

Conclusions and Summary

The major splits in ethereum, bitcoin, and bitcoin cash illustrate that the cryptocurrency ecosystem is more than a space for technological innovation; it is a testing ground for fundamental questions about freedom and governance. These developments provide insight into tensions between competing values such as decentralization, privacy, transparency, and control—tensions that shape how technological decisions are made and implemented.

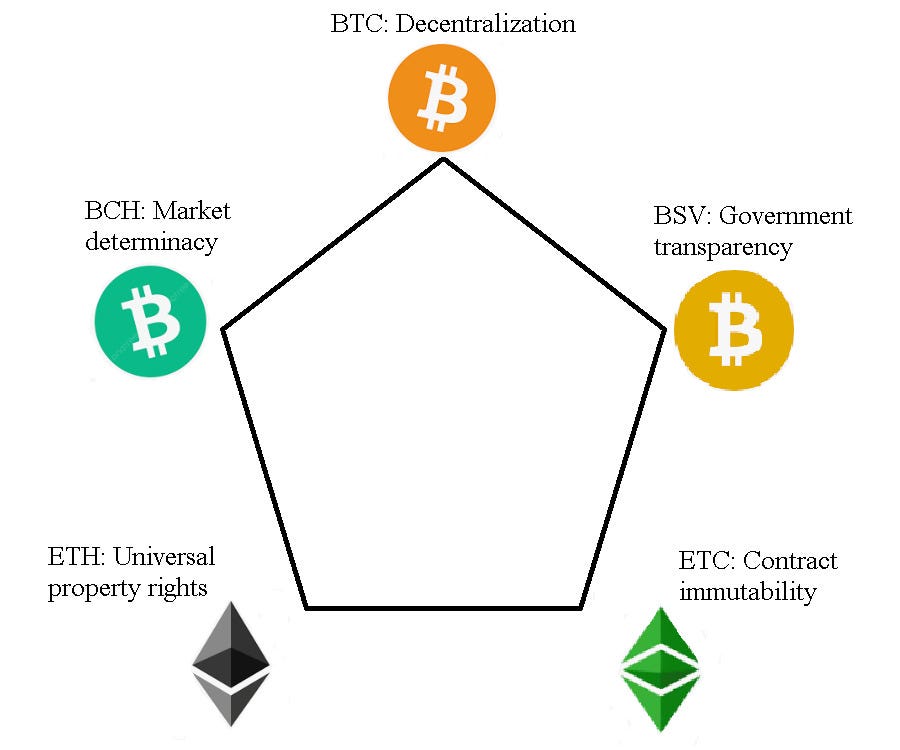

Figure 2. Five pillars of freedom, manifested in the cryptocurrency wars

In the cryptocurrency space, freedom emerges as a multidimensional concept rather than a singular notion. While all networks pursue freedom and agree on its fundamental components, each prioritizes a specific element above all others (see figure 2):

BTC: Decentralization, which serves as a safeguard against government control

BCH: Market determinacy, emphasizing the removal of artificial constraints

ETH: Protection of universal property rights

ETC: Immutability of contracts

BSV: Governance transparency

Disputes within the cryptocurrency space highlight the deep connection between technology and social values. Every technical decision—whether regarding block size, consensus mechanisms, or smart contracts—reflects underlying priorities. The trade-offs between censorship resistance and efficiency, immutability and community protection, or personal privacy and public transparency illustrate how blockchain architectures embody distinct social and political philosophies. Looking ahead, these conflicts and forks demonstrate that blockchain networks are not perfect solutions to all economic and societal challenges. Instead, they serve as platforms for experimentation, allowing diverse technological and ideological models to be tested under real-world conditions. The decentralized nature of cryptocurrency fosters an open market for competing ideas, resulting in an ecosystem where different approaches to freedom, decentralization, and efficiency coexist.

In traditional centralized organizations, technological decisions are typically made internally by executives or technical leadership. In contrast, within the cryptocurrency ecosystem, these discussions are often decentralized, involving developers, miners, investors, and users. Moreover, unlike in centralized environments where only one solution is ultimately adopted, the cryptocurrency space allows multiple ideas to exist simultaneously. Competing networks can evolve in parallel, each serving different communities and use cases. This structure enables individuals to choose the technological framework that best aligns with their values while observing the evolution of alternative approaches. As a result, the cryptocurrency ecosystem functions as an open laboratory for financial and technological freedom.

Importantly, the emergence of a dominant network does not diminish the significance of competing ideologies. Rather, it suggests that unifying those who prioritize financial sovereignty under a single, widely adopted cryptocurrency may be more effective in preserving freedom than any individual ideological stance. As we emphasized at the beginning of the article, the fork itself imposes a heavy cost on users, miners, and developers. The fact that the community eventually converged on a single coin in each case indicates that the conflicts were not entirely irreconcilable. The financial cost of a split, which is a burden on freedom in its own right, proved to be a more significant factor than an uncompromising adherence to a specific ideology of freedom.

References

Alden, Lyn. 2023. Broken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It Better. N.p.: Timestamp Press. Google Scholar

Ammous, Saifedean. 2018. The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. Google Scholar

Antonopoulos, Andreas M. 2017. Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Cryptocurrencies. 2nd ed. Sebastopol, Calif.: O’Reilly. Google Scholar

———. 2022. Mastering the Lightning Network: A Second Layer Blockchain Protocol for Instant Bitcoin Payment. Sebastopol, Calif.: O’Reilly. Google Scholar

Bier, Jonathan. 2021. The Blocksize War: The Battle over Who Controls Bitcoin’s Protocol Rules. Self-published. Google Scholar

Bitcoin Cash Podcast. n.d. “What about Privacy on Bitcoin Cash?” Accessed August 25, 2025. https://bitcoincashpodcast.com/faqs/BCH/what-about-privacy-on-BCH.

Brothwell, Ryan. 2023. “Unlocking Transparency and Accountability: NFTs in Government.” BSV Blockchain. July 28, 2023. https://bsvblockchain.org/unlocking-transparency-and-accountability-nfts-in-government/.

Buterin, Vitalik. 2014. “A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform.” Ethereum white paper. https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper/.

CoinMarketCap. n.d. “Ethereum Price Index.” Dataset for 2016–25. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/ethereum/?_t=1762884272123.

Cuen, Leigh. 2017. “Why Some People Love Bitcoin Cash.” International Business Times, August 22, 2017. https://www.ibtimes.com/why-some-people-love-bitcoin-cash-2581403.

De Filippi, Primavera, and Aaron Wright. 2018. Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674985933. Google Scholar

Lewis, Emily. 2024. “What Is Bitcoin SV? History of Bitcoin’s Most Controversial Fork.” DailyCoin, September 28, 2024. https://dailycoin.com/what-is-bitcoin-sv-history-of-bitcoin-controversial-fork/.

Poon, Joseph, and Thaddeus Dryja. 2023. The Bitcoin Lightning Network: Scalable Off-Chain Instant Payments. Self-published. Google Scholar

Popper, Nathaniel. 2016. “A Hacking of More than $50 Million Dashes Hopes in the World of Virtual Currency.” New York Times, June 18, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/18/business/dealbook/hacker-may-have-removed-more-than-50-million-from-experimental-cybercurrency-project.html.

———. 2017. “Some Bitcoin Backers Are Defecting to Create a Rival Currency.” New York Times, July 25, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/business/dealbook/bitcoin-cash-split.html.

Price, Rob. 2016. “Digital Currency Ethereum Is Cratering amid Claims of a $50 Million Hack.” Business Insider, June 17, 2016. https://www.insider.com/dao-hacked-ethereum-crashing-in-value-tens-of-millions-allegedly-stolen-2016-6.

Reiff, Nathan. 2023. “Bitcoin Gold: Distribution, Protection, and Transparency.” Investopedia. November 3, 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/tech/what-bitcoin-gold-exactly/.

———. 2024. “Bitcoin vs. Bitcoin Cash: What’s the Difference?” Investopedia. May 12, 2024. https://www.investopedia.com/tech/bitcoin-vs-bitcoin-cash-whats-difference/.

Shen, Muyao. 2020. “Bitcoin Cash Has Split into Two New Blockchains, Again.” CoinDesk. November 15, 2020. https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2020/11/15/bitcoin-cash-has-split-into-two-new-blockchains-again.

Siegel, David. 2016. “Understanding the DAO Attack.” CoinDesk. June 25, 2016. https://www.coindesk.com/learn/understanding-the-dao-attack.

Szabo, Nick. 1997. “Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks.” First Monday 2 (9): e548. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v2i9.548. Google Scholar

Ver, Roger, and Steve Patterson. 2024. Hijacking Bitcoin: The Hidden History of BTC. Self-published. Google Scholar

Vigna, Paul. 2015. “BitBeat: Blockstream Releases Liquid, First ‘Sidechain.’” Moneybeat (blog), Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2015. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-MBB-42432.