Fairness Stalls Deals and Creative Reframing Saves Them

The Soft Belly of Negotiation

Negotiations often break down not because the numbers don't work, but because people do. Beneath spreadsheets and term sheets lie emotions, narratives, and principles that can derail even the most promising discussions. I've seen this firsthand, multiple times over the years. In my own work advising on complex transactions, I've witnessed how even trivial moral standoffs can block deals worth millions. One of the most common culprits is a contested sense of fairness.

When each party believes their position is the righteous one, it creates a moral standoff, with fairness becoming both sword and shield. The negotiation turns from value creation to value defense. Even proposals that would clearly improve both parties' outcomes get rejected if they seem unjust. In the classic ultimatum game, people routinely refuse offers they view as unfair - even when rejection means walking away empty-handed [1].

I've been involved in and witnessed many cases where the parties had aligned perfectly on price and scope, but the deal broke down over seemingly minor details, like who should cover legal fees, or what exact wording to use in a termination clause. These impasses were rarely about substance and almost always about dignity, symbolism, or perceived moral standing. In some instances, these seemingly inconsequential terms (formalities, or symbolic gestures) became stand-ins for deeper moral or emotional claims. What appears trivial on the surface often functions as a proxy for perceived legitimacy or control. These impasses hardly ever about the details themselves, but about what those details represent to each party.

I like to call these negotiation's soft belly: the fragile, often irrational space where emotions, identities, and perceived justice overwhelm interest-based reasoning. But this vulnerability also holds the key to resolution. If addressed with creativity and curiosity, the soft belly can become the lever that opens the door to hidden value.

From Positions to Interests

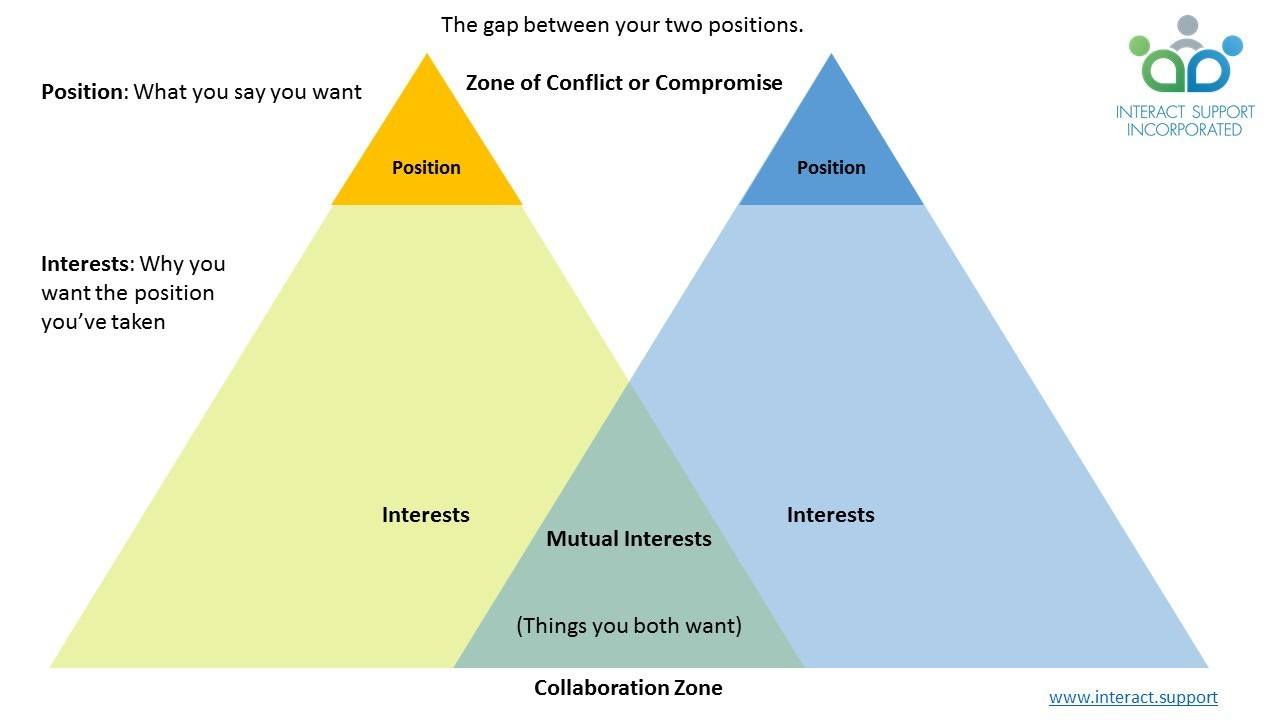

To understand how deadlocks occur, and how to overcome them, we need to revisit the foundations of negotiation theory. Fisher and Ury's groundbreaking work on principled negotiation emphasized the distinction between positions (what people say they want) and interests (why they want it) [2]. Positions are explicit and often rigid; interests are typically implicit, layered, and negotiable. When negotiators focus on positions, they fall into distributive thinking: the assumption that value is fixed, and that one party's gain must come at the other's expense. This zero-sum mindset narrows the bargaining range and hardens stances.

However, if parties probe deeper into interests, they often uncover differences in valuation that can be exploited to mutual benefit [3]. These differences define the Zone of Possible Agreement (ZOPA) [4]. Sometimes, that zone is invisible at the outset. What appears to be a negative bargaining zone, where no agreement seems possible, can actually hide creative trade-offs that would satisfy both sides.

Three psychological biases often stand in the way:

Fairness bias: The tendency to reject objectively beneficial outcomes if they feel unjust, often rooted in ego or identity.

Anchoring: Fixation on an initial demand or idea that distorts future judgment [5].

Loss aversion: The cognitive tendency to fear losses more than equivalent gains, which can make concessions feel painful even when rationally sound.

Negotiators who understand and anticipate these biases can shift the game from deadlock to design.

Here are two real cases I’ve dealt with in recent months that illustrate the point:

Case Study 1: The Four-Day Grace Period

Consider a real estate deal where the seller demanded a 7-day grace period to vacate the apartment after the official closing date, claiming “that’s the norm”; despite there being no real risk of delay. His position seemed not to have been based on any visible economic logic, but on a sense of fairness. He saw this request as a basic gesture of respect.

The buyer, on the other hand, initially insisted on a strict closing date. He had to vacate his own apartment within 4 days of closing and wanted to be sure the new place would be ready on time.

The two sides hit a deadlock. The seller wanted 7 days. The buyer insisted the apartment must be vacant on closing, zero grace days. Both considered walking away from the deal.

Then, a little savage bird whispered in the buyer's ear: your magic number is 4, not 0. The buyer wasn’t planning to move in until 4 days after closing anyway. So what if he offered the seller exactly 4 days? For the buyer, the result was the same - he’d still move in on schedule. But for the seller, the buyer was “giving in” and flexing from zero days to four. It felt like a meaningful gesture of fairness.

0-4 was the dead zone; the excess fat no one wanted anyway. 4-7 is where the real magic of subjective preferences coinciding was taking place.

That offer changed the entire dynamic. What had been a tense negotiation suddenly became a friendly conversation. The seller, feeling respected, became more flexible on other issues. A deal that looked like it was about to collapse ended successfully.

This case clearly shows how the same thing can be valuable to one side and worthless to the other, what is commonly referred to as “valuation asymmetry.”

For the seller, those four days were about dignity. “At least I got some time to get organized.”

For the buyer, they made no difference at all; he planned to move on the 5th day anyway anyway. Once the buyer saw that, he realized he’d struck gold - he could give away something meaningless to him and get something big in return. He also defused an anchored fairness bias by agreeing to the seller's frame rather than challenging it.

That’s what negotiators call logrolling: finding points where what’s cheap for you is expensive for them, and trading on that [6].

The deal got done: and more than that, the dynamic changed. They stopped seeing each other as adversaries and started acting like allies.

Case Study 2: Commission Turned Apartment

In a more complex example, a broker had earned a sizable commission on a property development deal. The developer, strapped for cash due to broader market conditions, resisted payment. The broker viewed nonpayment as a betrayal; the developer viewed the demand as insensitive to commercial realities. Each side felt morally justified, and insulted by the other.

After several tense exchanges, they found a workaround. The developer offered the broker a steep discount on an apartment in a separate project. The gap between the market price and the discounted price equaled the commission owed. This wasn't just an asset swap, it was a conceptual shift.

The reframing transformed the negotiation from a demand for payment to a collaborative investment opportunity [7]. The broker got a valuable asset he could either flip or hold. The developer converted a liability (unpaid debt) into an asset sale (inventory reduction). Most importantly, neither side had to say, "I gave in."

Loss aversion played a central role. Writing a check felt like a loss for the developer, but giving a discount on unsold property felt like a smart move. The broker, too, overcame his anchored expectation of cash by seeing the apartment as a potentially superior form of compensation. In fact, by turning the commission into a discounted investment, he arguably improved his upside.

This kind of trade exemplifies integrative bargaining. The parties expanded the negotiation space beyond the initial dispute. They neutralized the fairness standoff by making it moot. Each side could claim they had acted reasonably and fairly without conceding their moral stance.

Surplus Realization; Perceived Legitimacy

In both examples, the negotiation moved from confrontation to co-creation. But spotting a hidden overlap is only part of the journey. The next step is realizing the surplus. That is, capturing and allocating it in a way that feels acceptable to both sides.

Perceived fairness remains critical. An efficient deal that feels exploitative will unravel. To ensure surplus realization, negotiators must actively manage how outcomes are perceived, not just what outcomes are achieved. This often involves:

Packaging concessions as gifts or acknowledgments rather than losses.

Allowing the other party to save face.

Leaving space for symbolic victories.

These elements allow people to maintain dignity and coherence in their narratives. As Max Bazerman notes, people don't just want a good deal; they want a deal that fits their self-image [8].

In the grace period case, the seller could say, "They respected my situation and gave me the dignity I deserved." The buyer could say, "I showed flexibility that cost me nothing but secured a smooth deal, and probably saved money by avoiding a protracted negotiation."

In the broker case, both sides could claim victory on their own terms. The developer could boast, "Instead of having to pay out cash, I got the broker to buy one of my properties." The broker could assert, "I got my full commission, secured a great price on prime real estate, and can easily flip it for more than I originally expected."

From an economic perspective, both agreements achieved Pareto efficiency; no party could be made better off without making the other worse off, representing the optimal allocation of resources given the constraints.

What ultimately defines a well-structured deal isn't simply that both sides benefit, but that both can explain (to themselves and others) why the outcome made sense.

When each party walks away feeling their core interests were acknowledged and their principles respected, the agreement stands a better chance of enduring.

Negotiator's Toolkit: Five Diagnostic Questions

What are the underlying interests and needs of each side? In other words, what do they really want or fear, beyond the positions they're arguing for? Move the focus from "Who is right?" to "What do we each truly need?"

Which issues do we value differently? What might be low-cost for me to give but high-value for them, and vice versa? This highlights potential trade-offs based on valuation asymmetry.

Can we add or link issues to create a package deal? Are there other goods, services, or terms, payment plans, timing adjustments, alternate forms of compensation, that we haven't considered? Expand the scope to reveal a new ZOPA where none existed.

Are we framing the negotiation in the best way? Is a fixation on "fairness" or a specific number is anchoring the discussion? If so, how could we reframe the proposal so it addresses core concerns? For example, would structuring an offer as a discount or an extra benefit make it more palatable due to loss aversion or pride?

"What would it take for you to say yes?" A direct, open-ended question posed to the other side which invites them to reveal conditional acceptances. It shifts the dynamic from rejection to problem-solving. The answer would flush out where hidden value or flexibility lies. Effectively, it could map out the pathway to agreement.

These questions redirect the conversation from moral standoff to practical solution and ultimately, to agreement grounded in mutual understanding.

Negotiations too often break down over symbolism or pride, and this kind of disciplined curiosity can create paths forward that are both efficient and humane. Succumbing to the temptation to argue over who's right wastes time. Asking what works gets results.

References

[1] Thompson, L. (2005). The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator. Prentice Hall.

[2] Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Harvard Law School.

[3] Lax, D. A., & Sebenius, J. K. (1986). The Manager as Negotiator. Free Press.

[4] Raiffa, H. (1982). The Art and Science of Negotiation. Harvard University Press.

[5] Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk." Econometrica, 47(2).

[6] "Logrolling Definition." Scotwork Global Glossary.

[7] "Reframing Obstacles as Opportunities." Aligned Negotiation Blog.

[8] Bazerman, M. H. (2006). Judgment in Managerial Decision Making. Wiley.

I really enjoyed this.

Your “soft belly” idea feels so relatable and spot on.

It feels like you’ve lifted the curtain on why deals stall,

and your real-world stories make it click.

I’m curious though.

How do you actually spot someone’s soft belly in a tense conversation?

And how do you reframe positions to uncover that hidden ZOPA in practice?

Thank you for posting this - it helped me crystallize some ideas I'd been turning around in my head for a while.